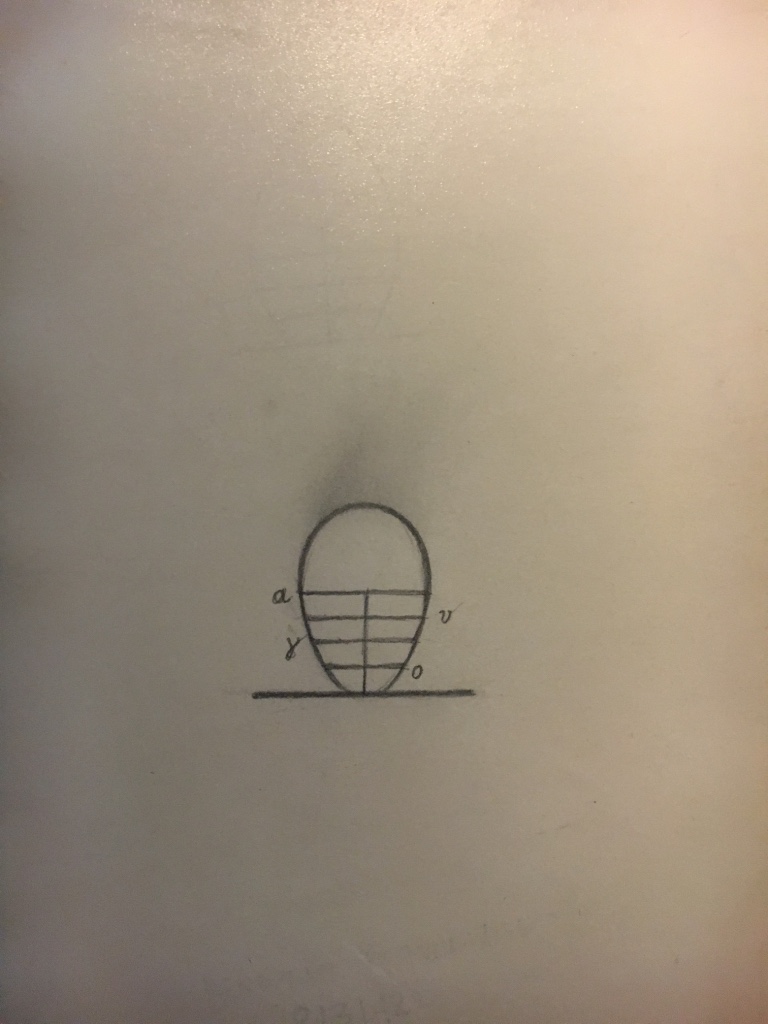

I. Egg-white

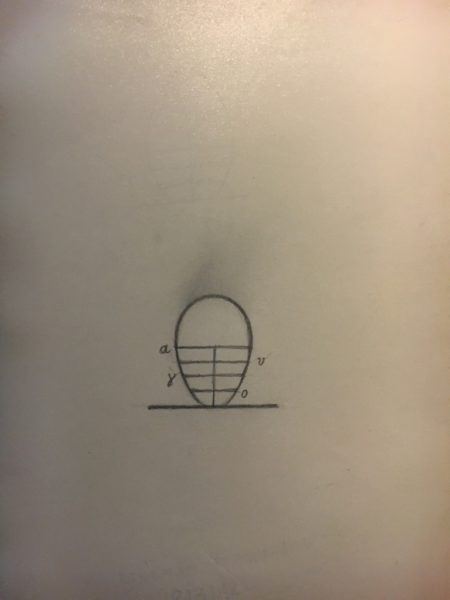

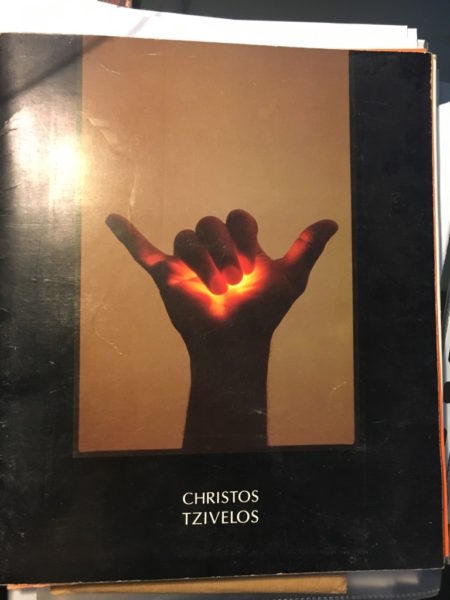

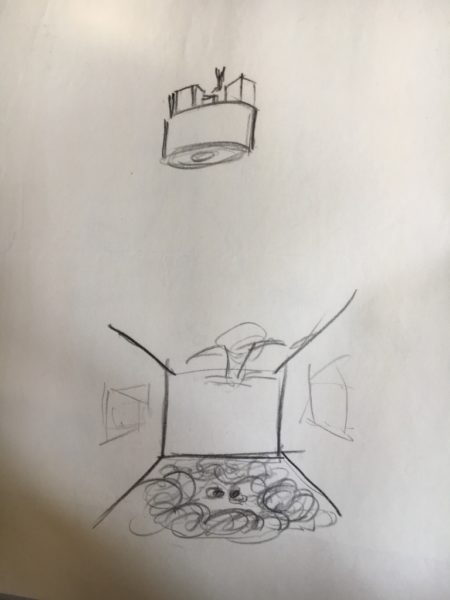

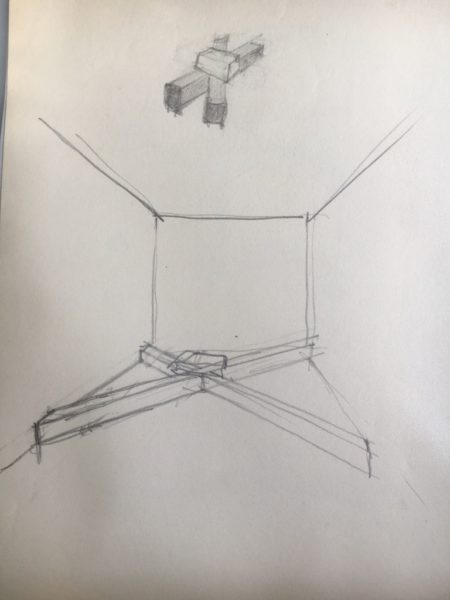

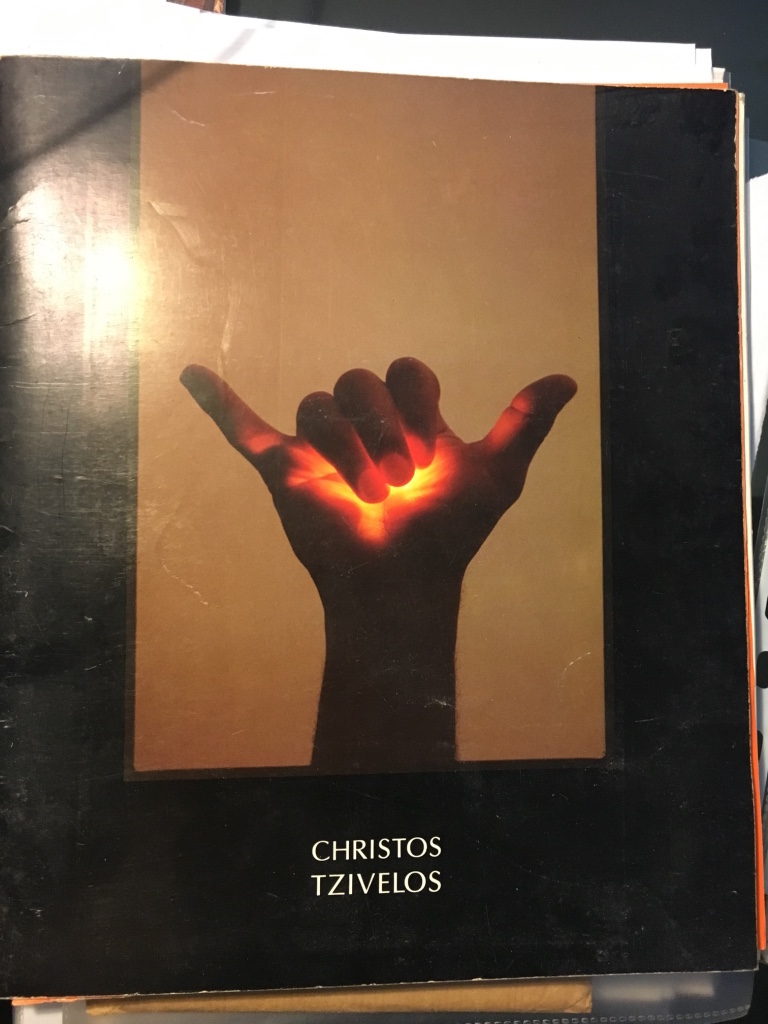

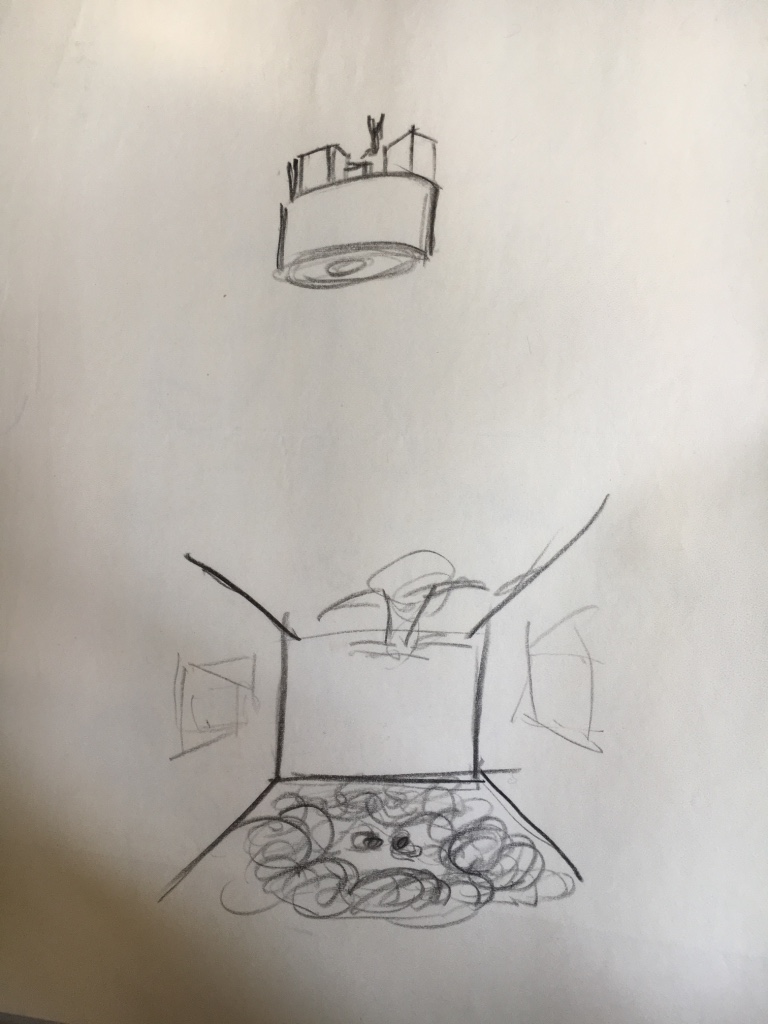

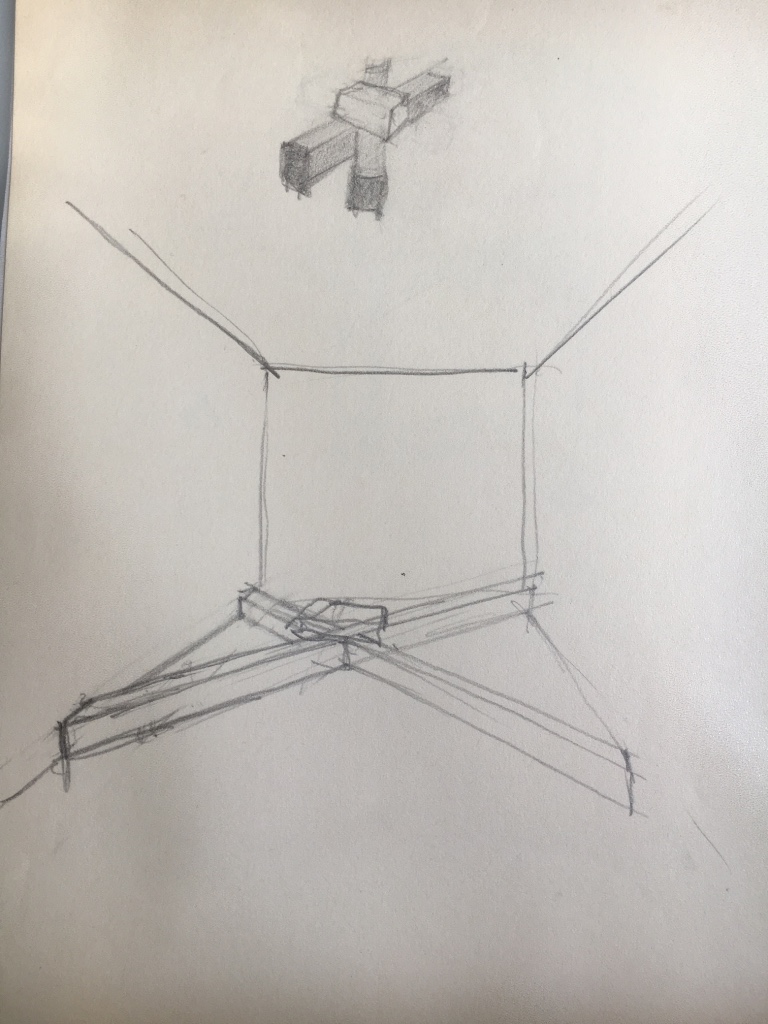

In many cosmogonies, some primordial being comes into existence by hatching from an egg commonly referred to as the “World egg.” In Orphic philosophy, the world egg breeds a hermaphroditic deity which in turn creates the other gods. In one of his drawings, Tzivelos has fertilized the egg with a black hole, which curator Bia Papadopoulou discusses in an essay published in 2017. Tzivelos’ womblike enclave, like hundreds of other drawings suggest, was a sectional view of a room, inside of which he conceived his sculptures. In his former home in Galatsi, which still houses many of his belongings: furniture, lamps, CDs, and books, a few remaining artworks now appear in three-dimensional space. Suddenly the off-white walls appear like the inside of an egg in the aftermath of its hatching. Tzivelos’ nephew Yiannis now resides in the house and has brought to it his own fertilizing objects, yet signs of their successive ownership have not eclipsed one another. Everything inside is loud of time, like items in a house museum in a home.

II. Parenthesis

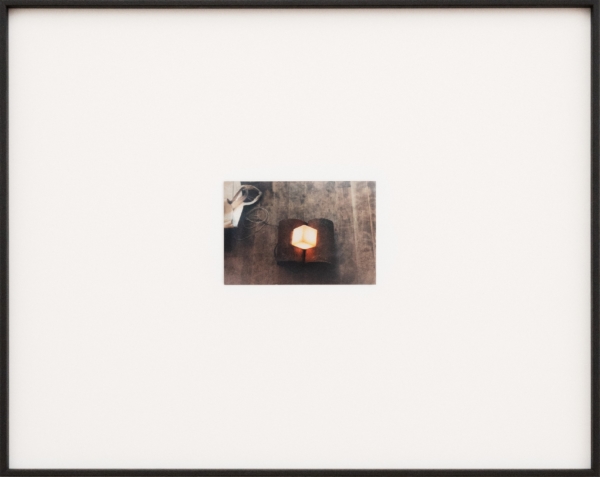

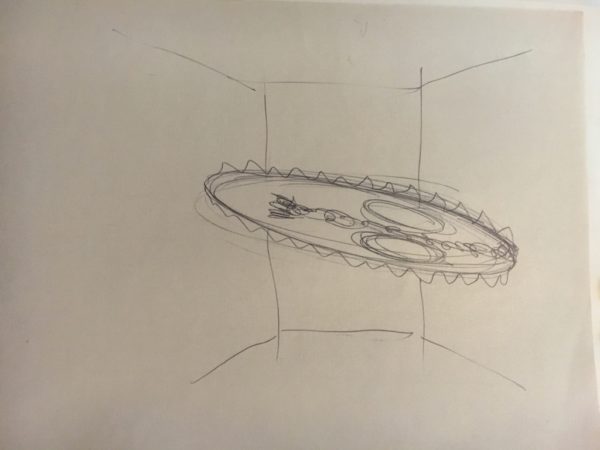

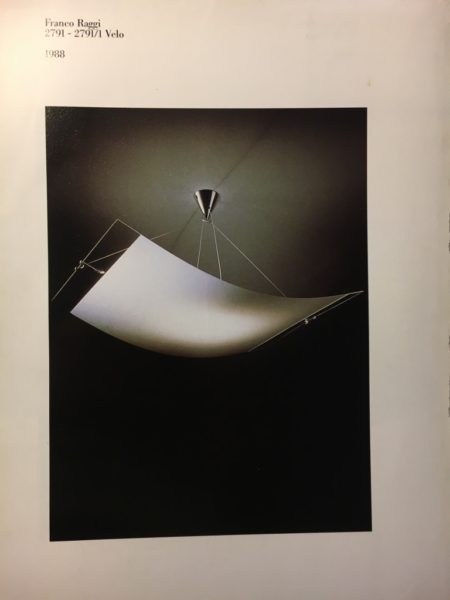

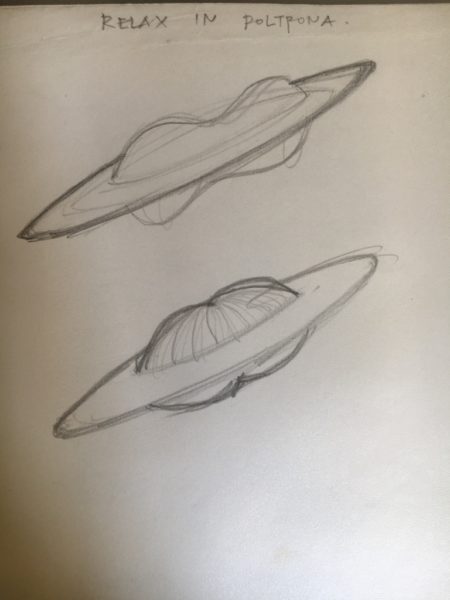

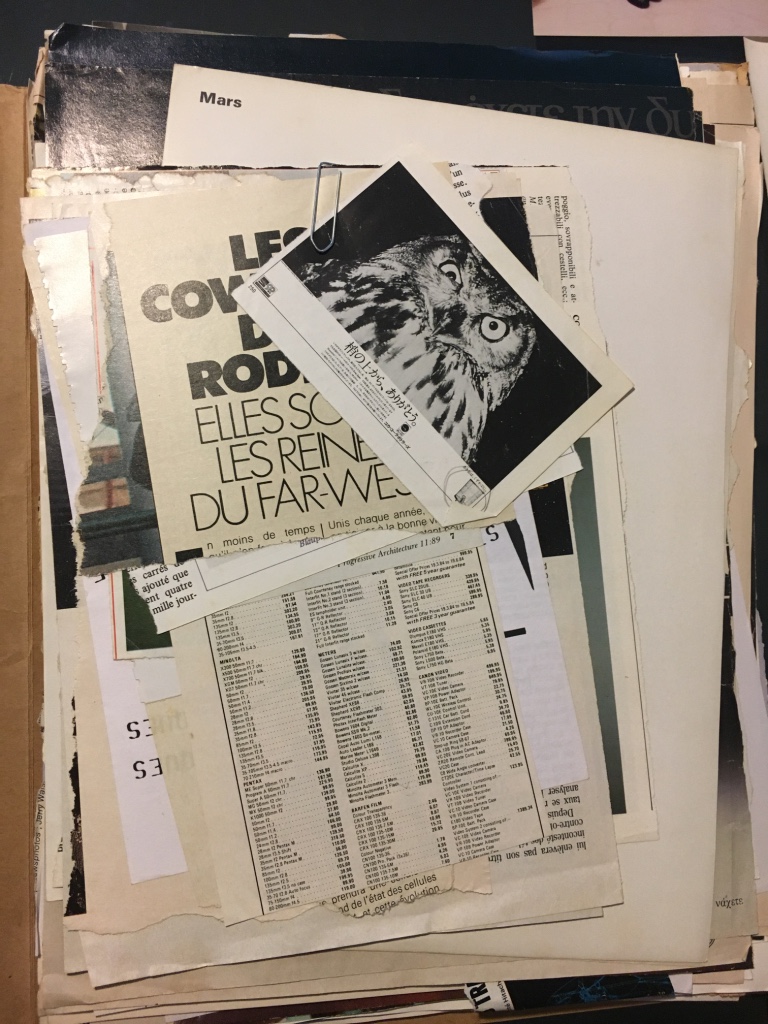

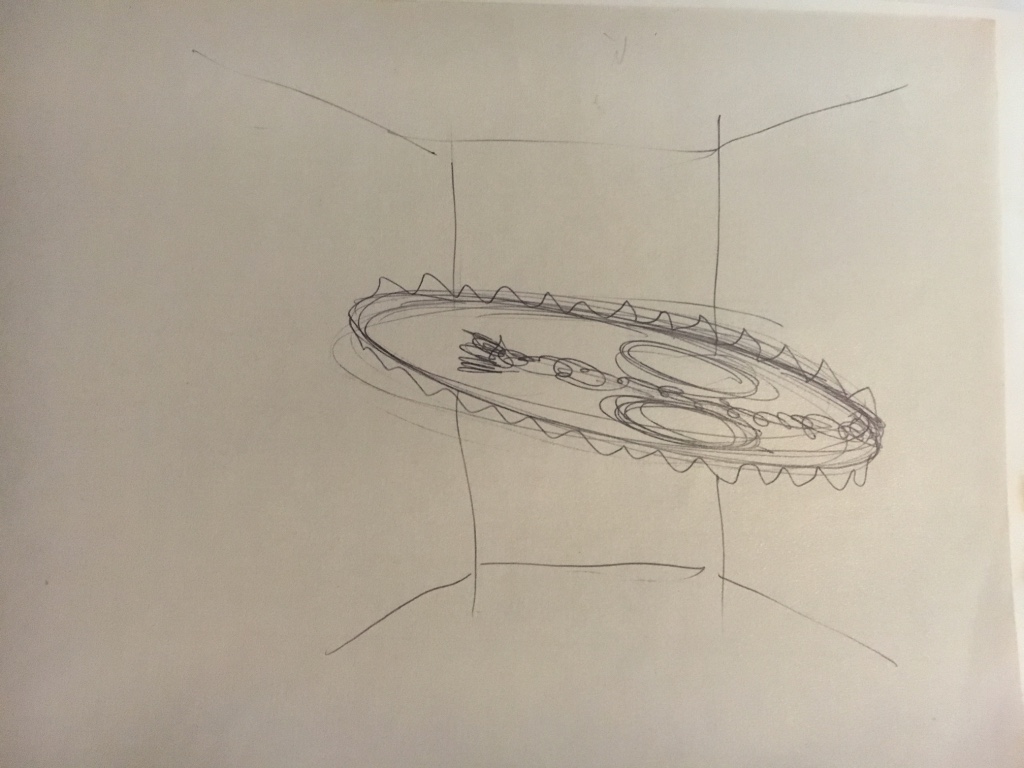

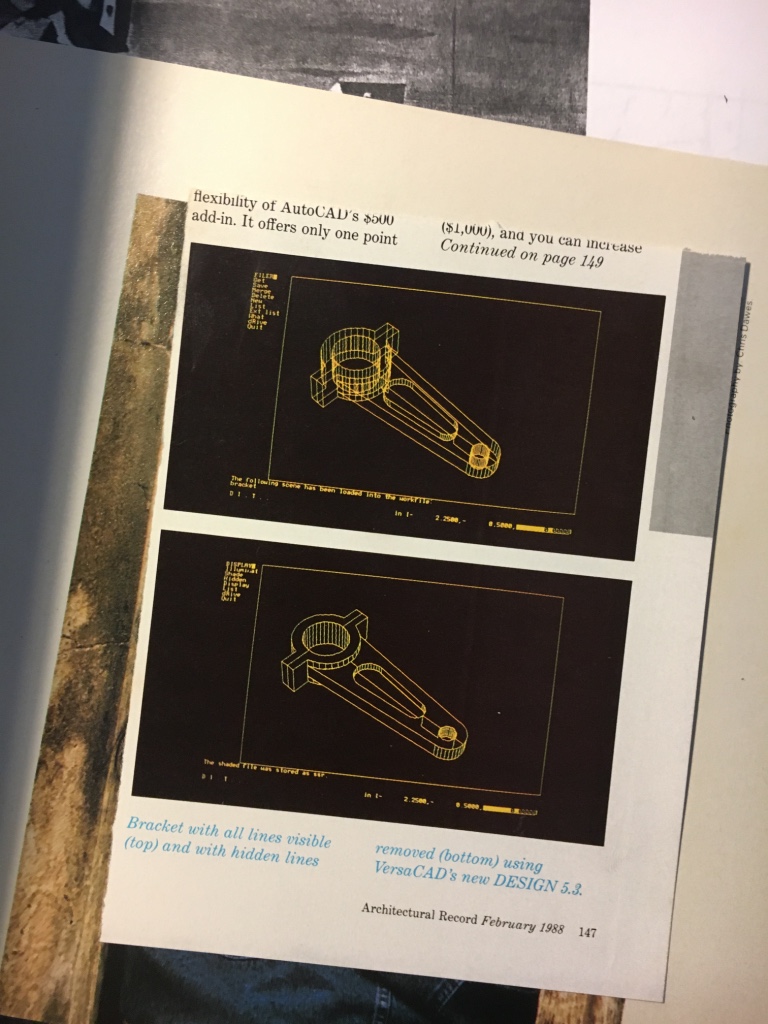

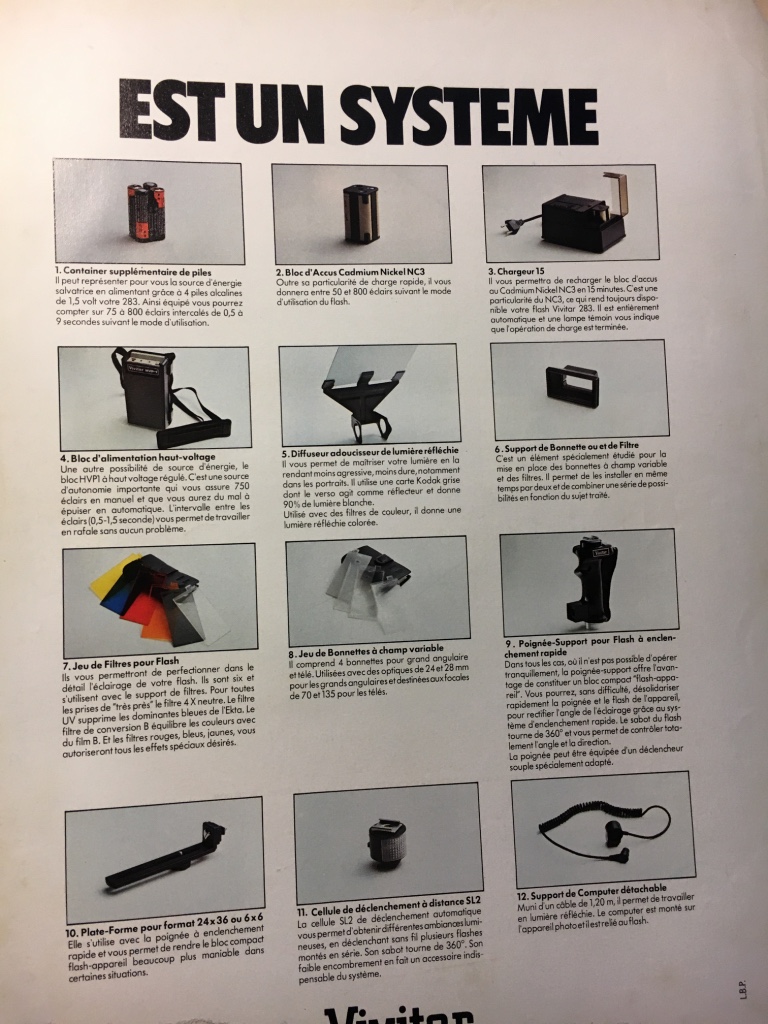

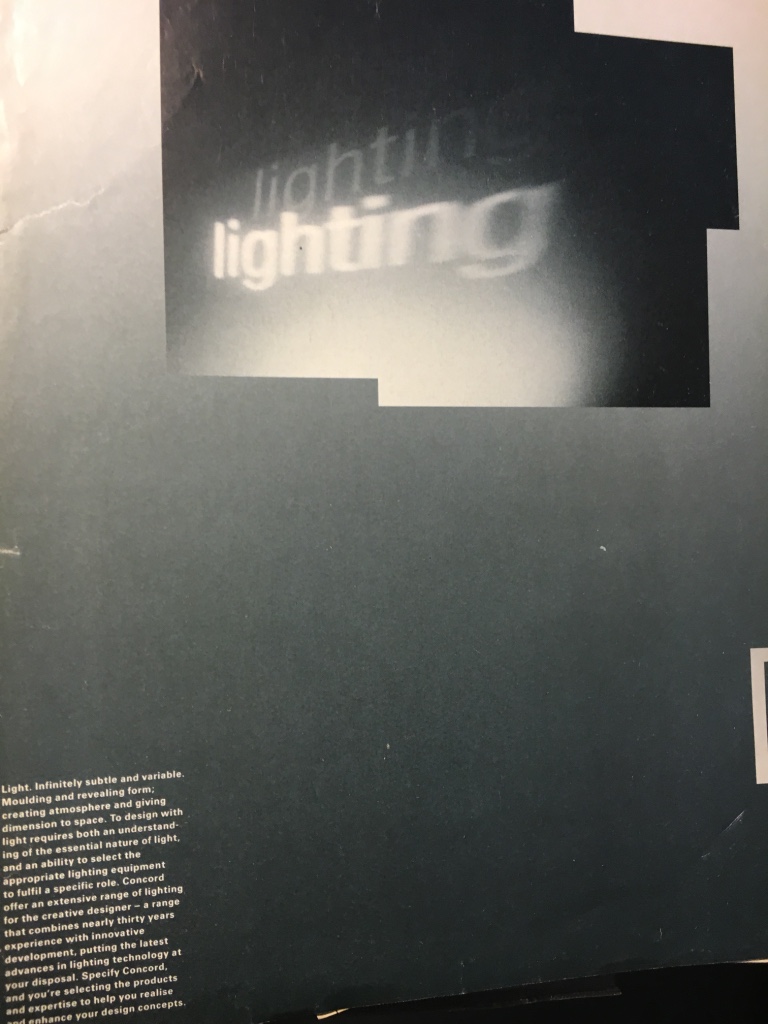

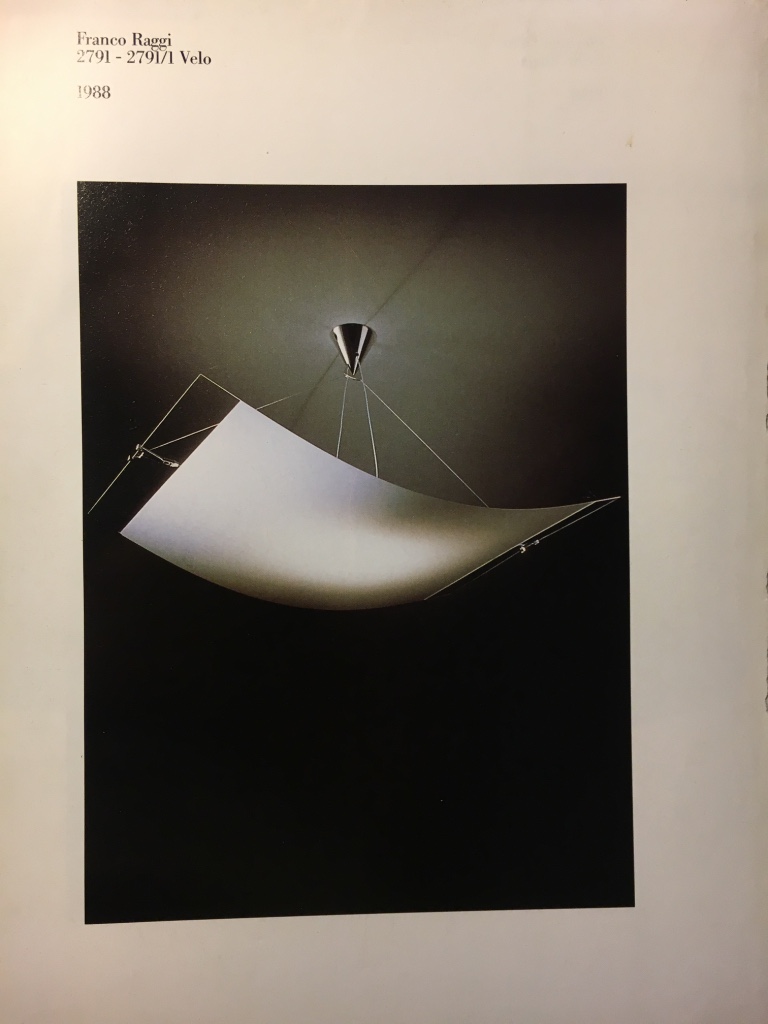

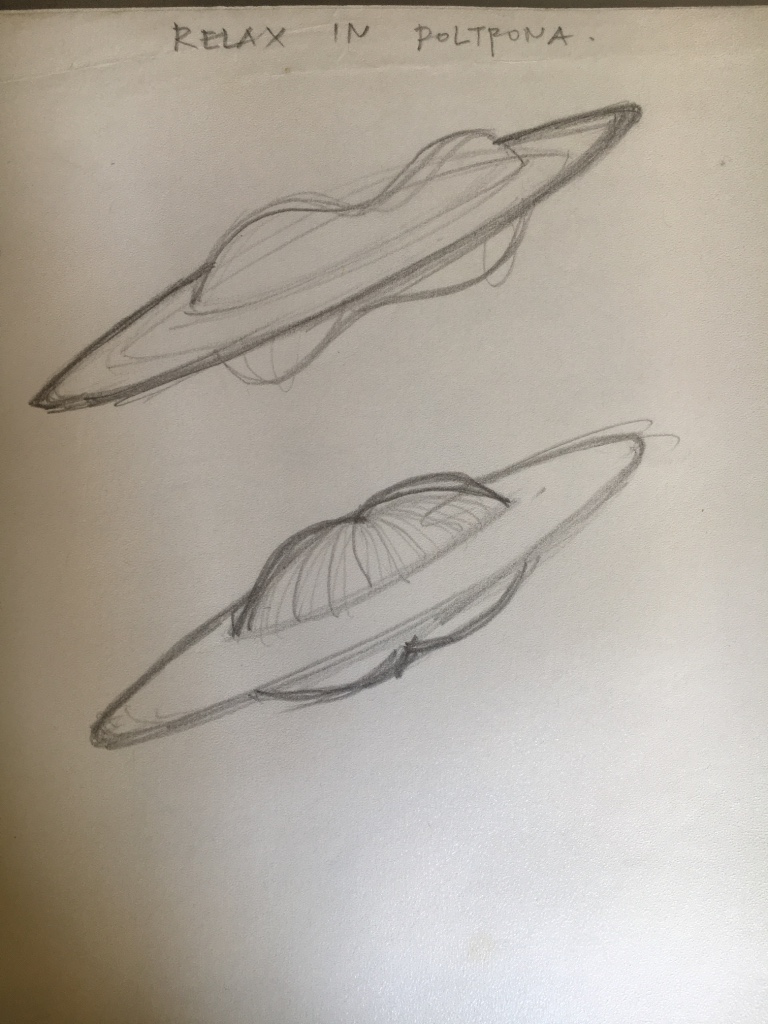

Tzivelos was enamored by interior design, which he’d also studied at the Doxiadis School in 1971. During my visit to the home in 2019, two of Achille Castiglioni’s and Pio Manzù’s ‘Parentesi’ lamps hung in the corner, next to a pair of Marcel Breuer’s ‘Wassily Chairs.’ In the bathroom, a rusted toilet paper holder that he’d designed, mirrored the rusted iron sheets from a 1994 installation that leaned against the wall in the courtyard. A collection of brass candleholders framed the floor below his ‘Light Fossils’ hanging on the wall above the TV. Behind his desk, a chair designed by his brother, locked in an Untitled drawing picturing a thick circle in graphite. The metal cabinets in the kitchen, which he’d also designed, echoed the metal architectures that were often part of his installations. Among his clippings, there were ads for Pierluigi Cerri’s ‘Mozia’ and Franco Raggi’s ‘Velo’ lamps, and other furniture and interior design ads; many were ripped around the photos, while others framed exclusively the texts. These vignettes spoke of light like odd instruction manuals where language reminiscent of scientific texts veers towards poetry by hollowing itself out of preoccupations with proof and accuracy:

“Light. Infinitely subtle and variable. Moulding and revealing form; creating atmosphere and giving dimension to space.”

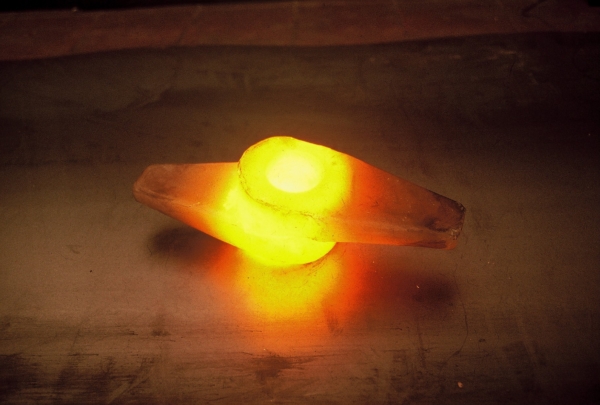

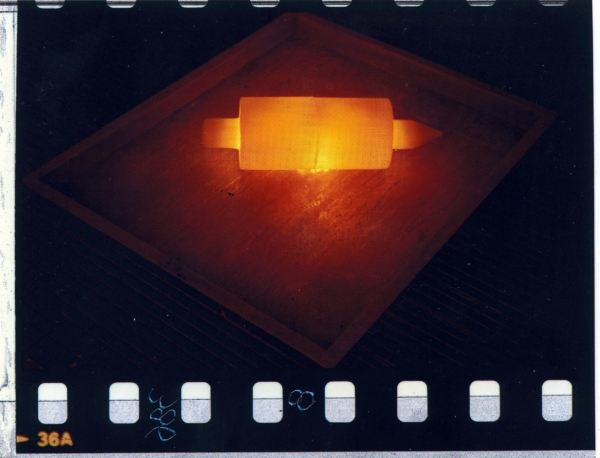

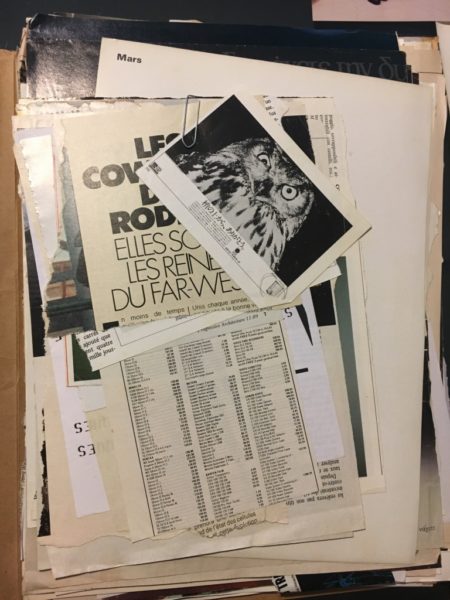

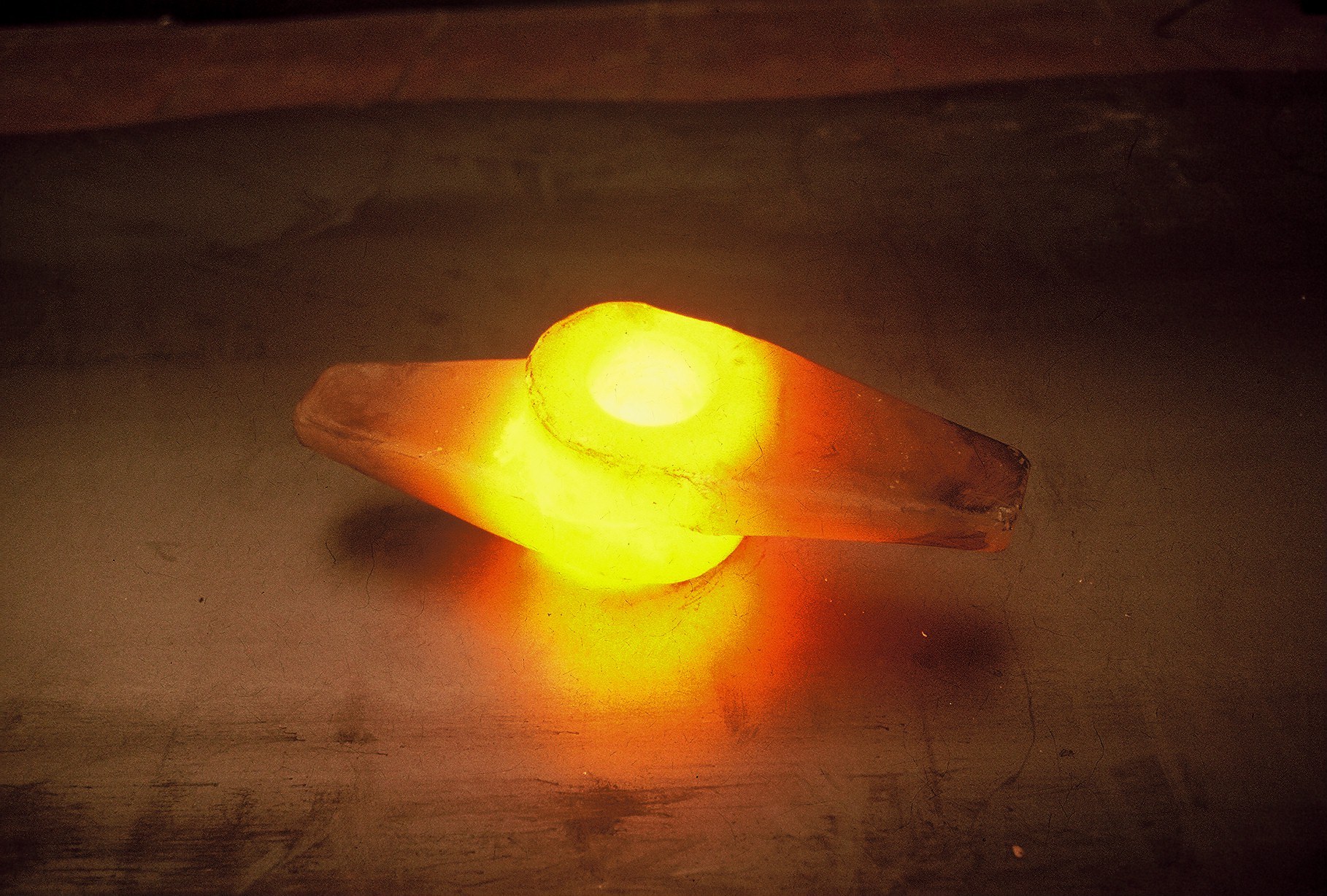

Other clippings, feature anvil-like shapes, in near direct correspondence with Tzivelos’ resin and wax installations; from 1983 onwards, when he begins to sculpt firmly with light, interior advertisement ads and scientific articles become an essential reference point.

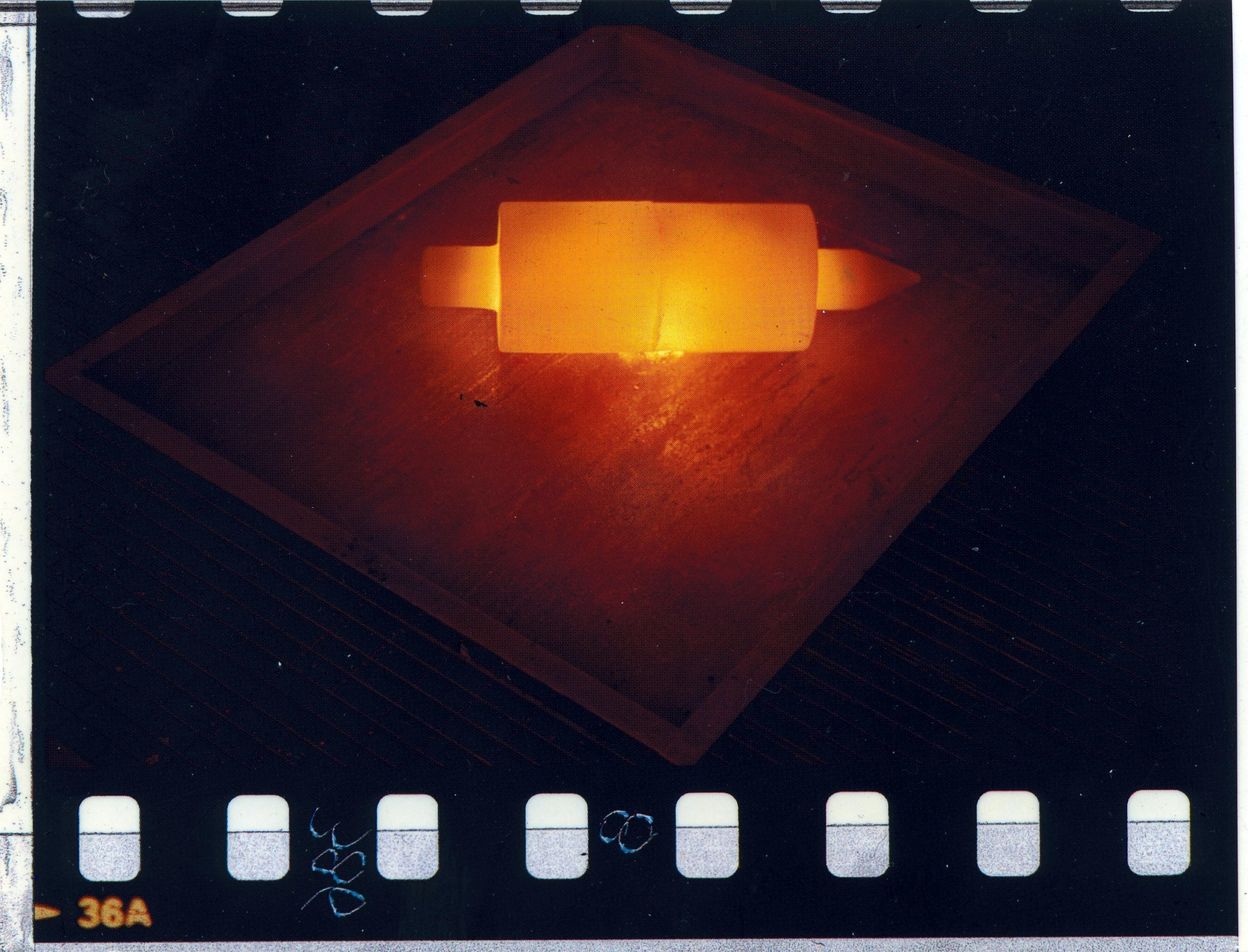

III. Halogen

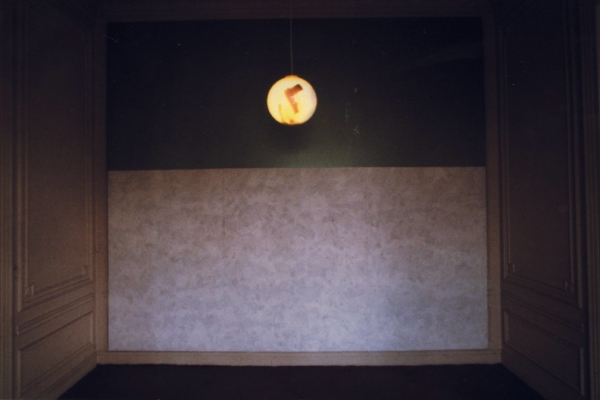

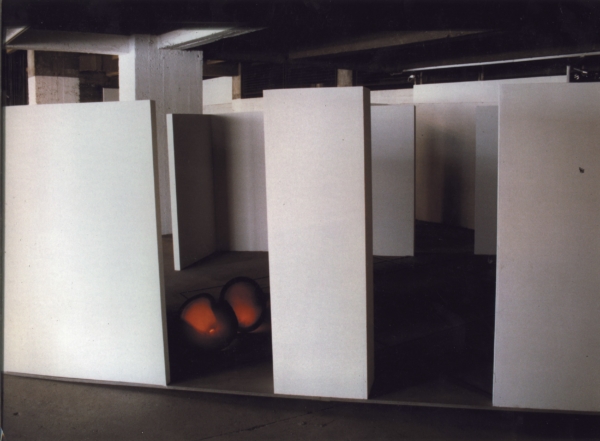

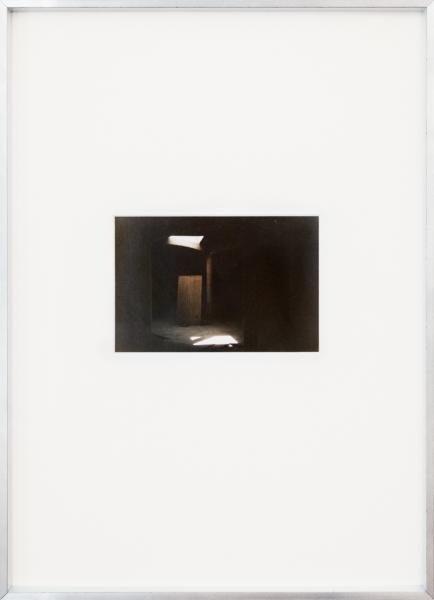

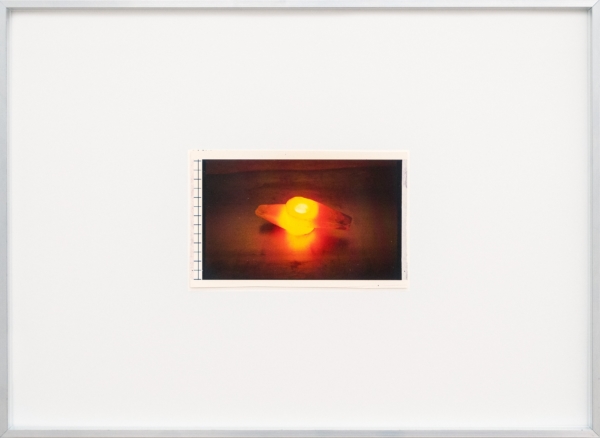

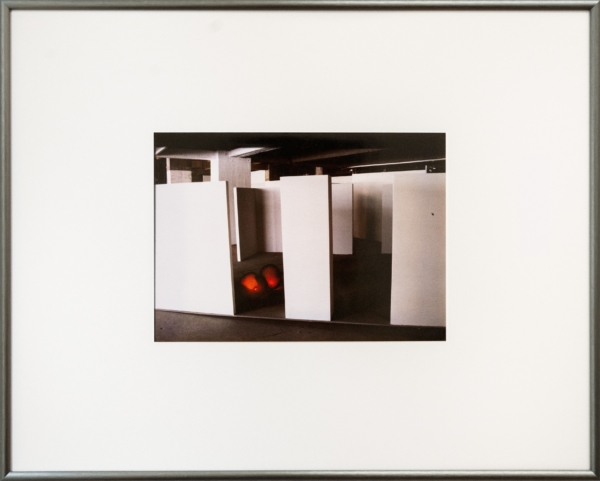

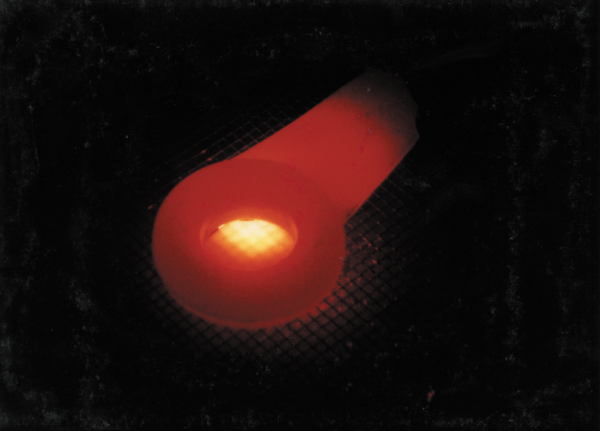

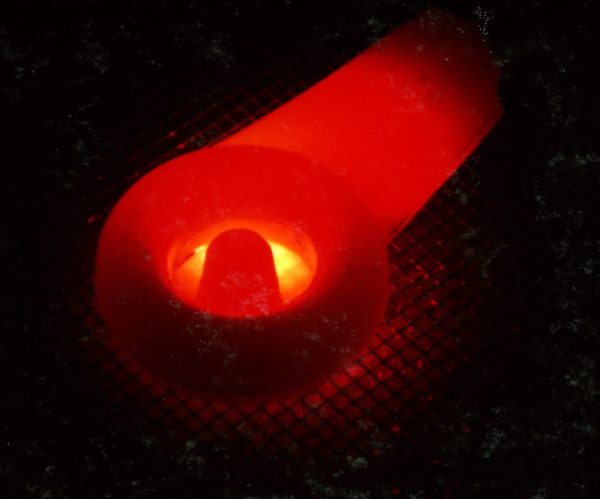

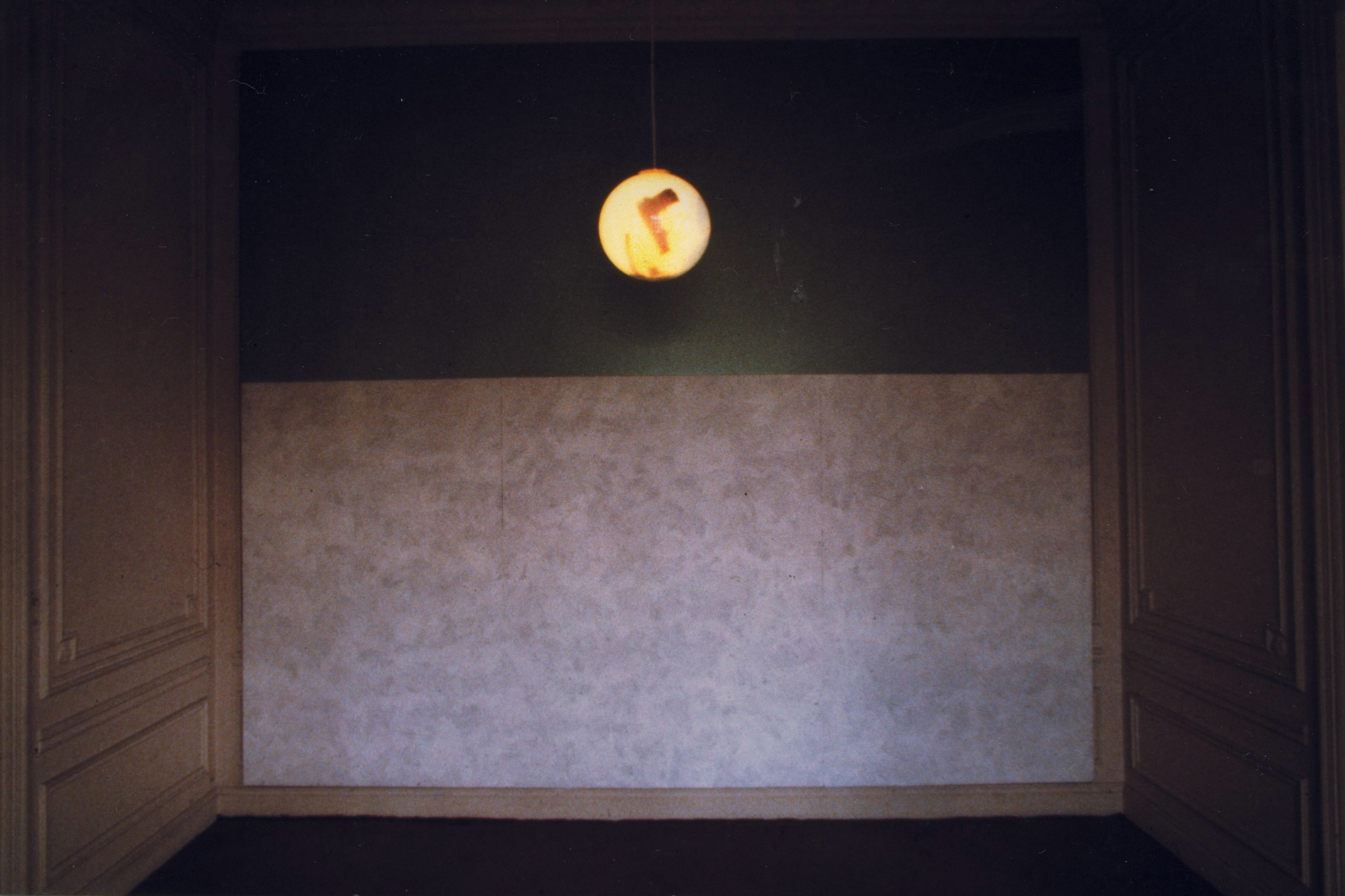

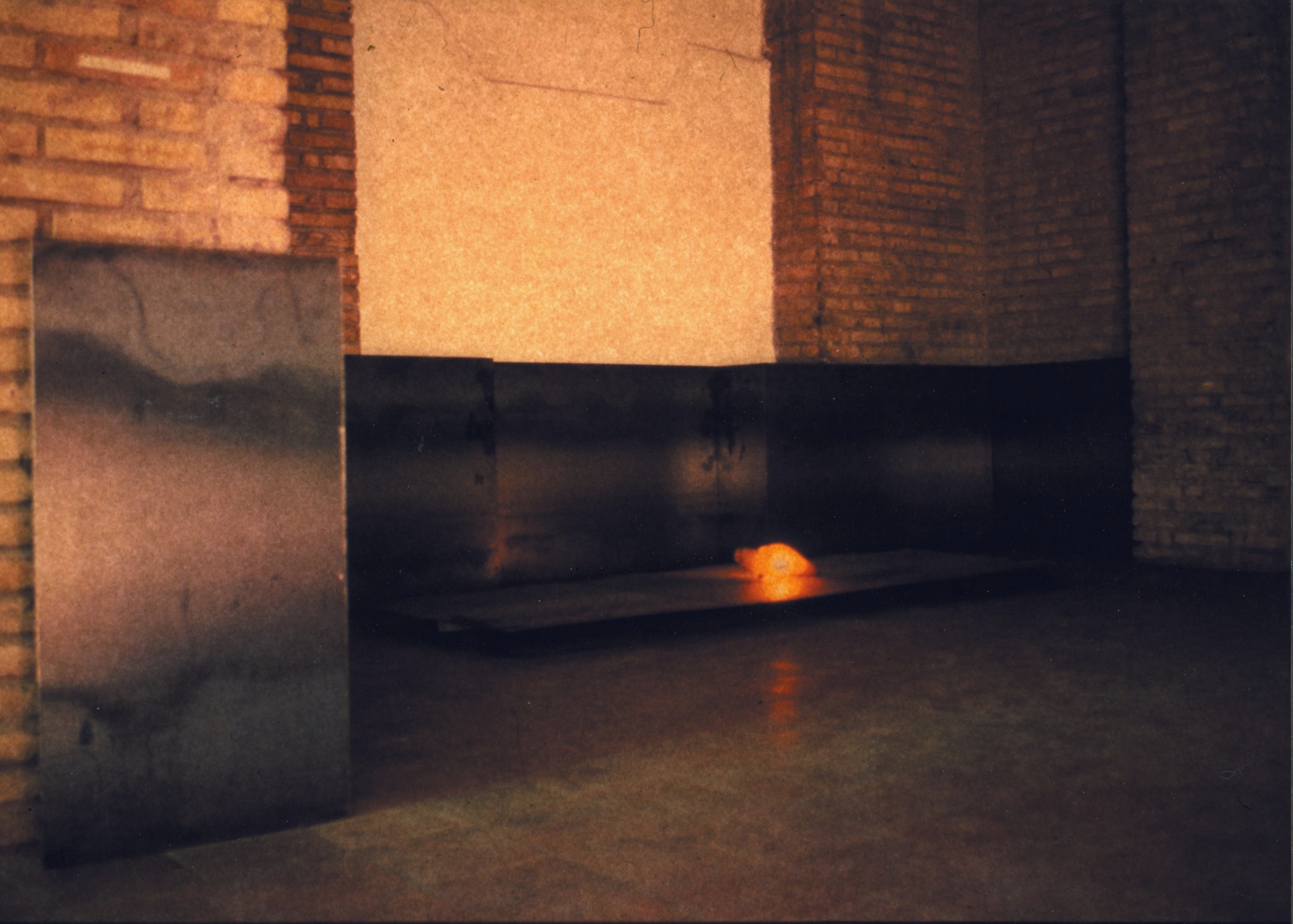

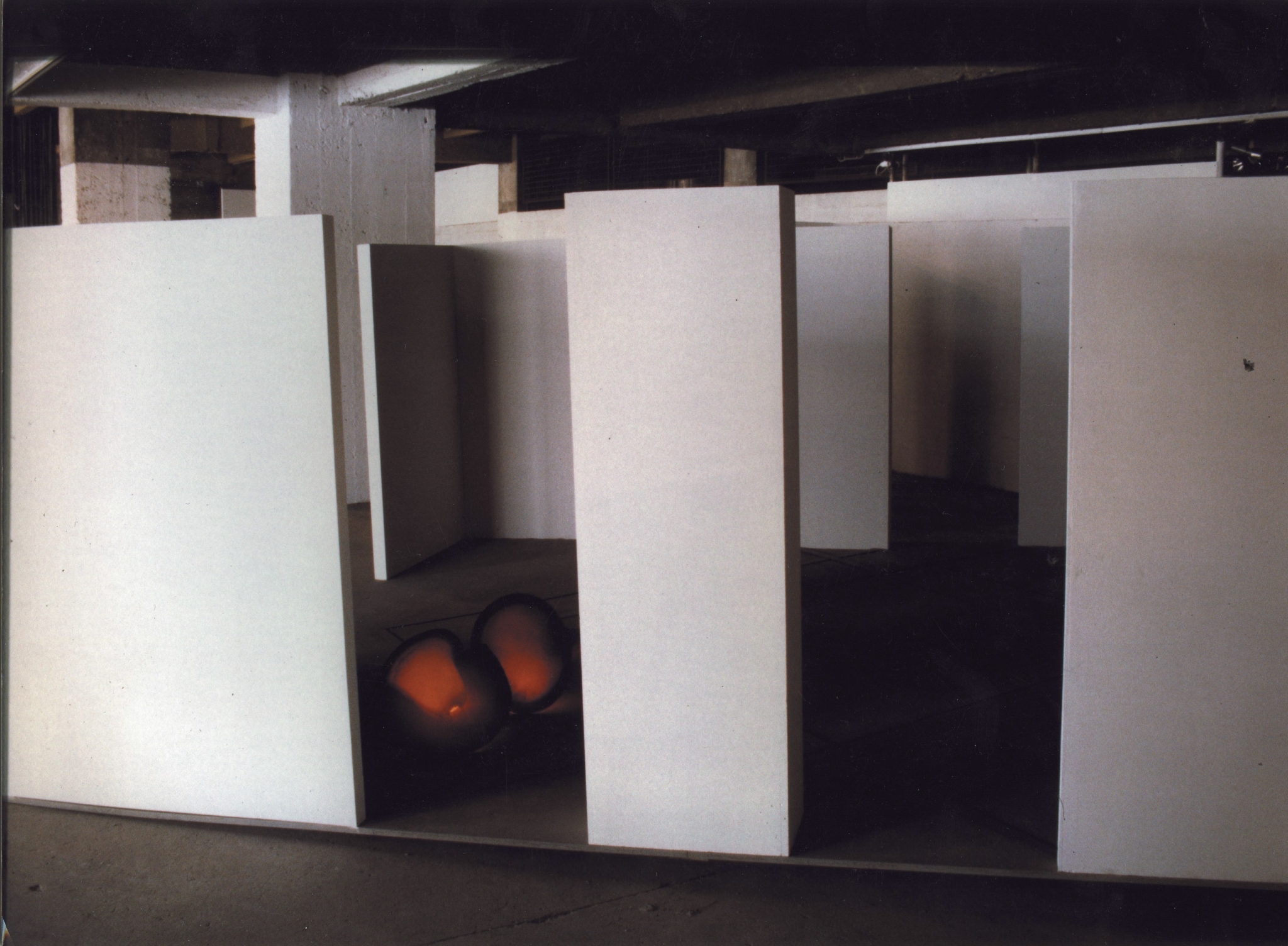

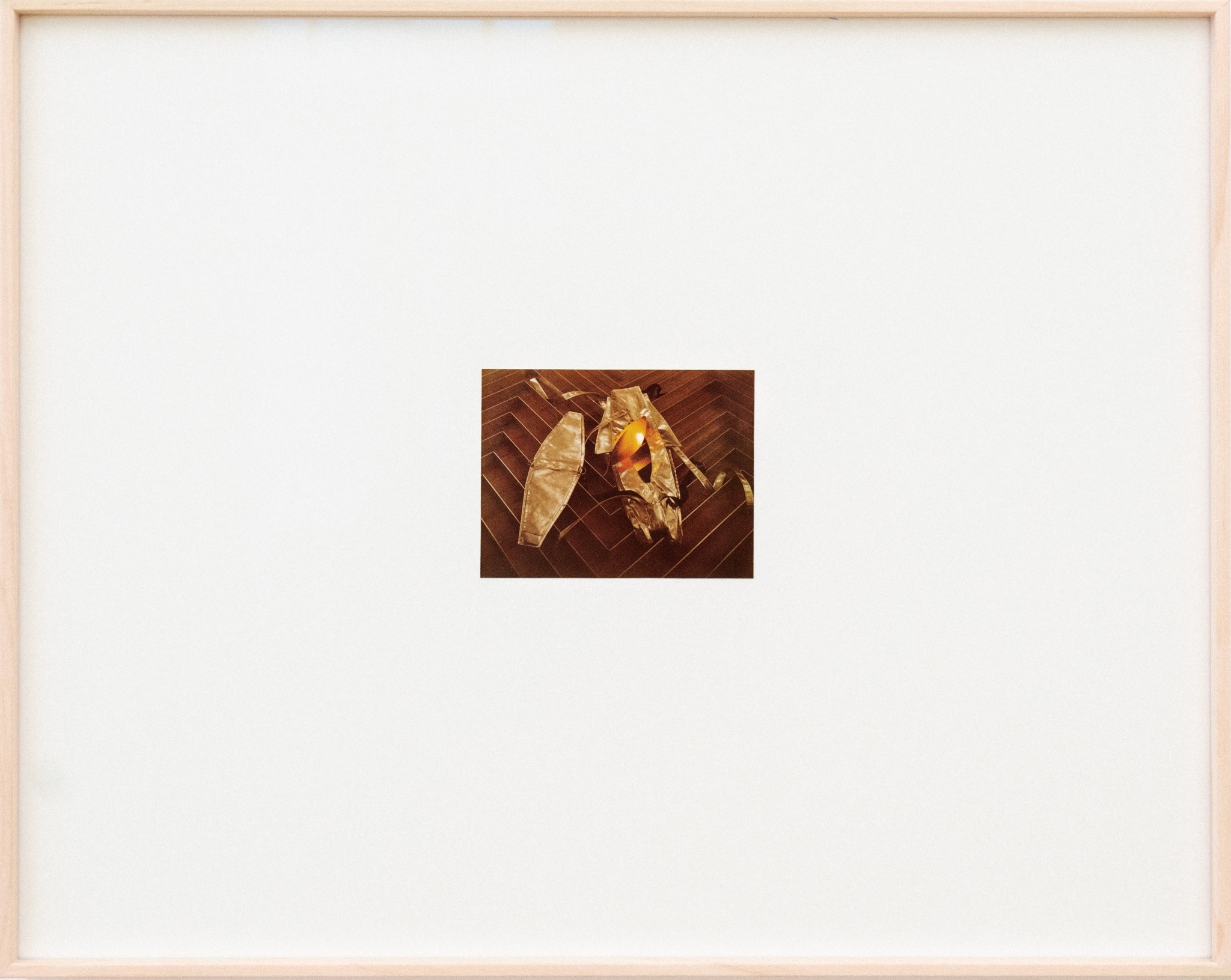

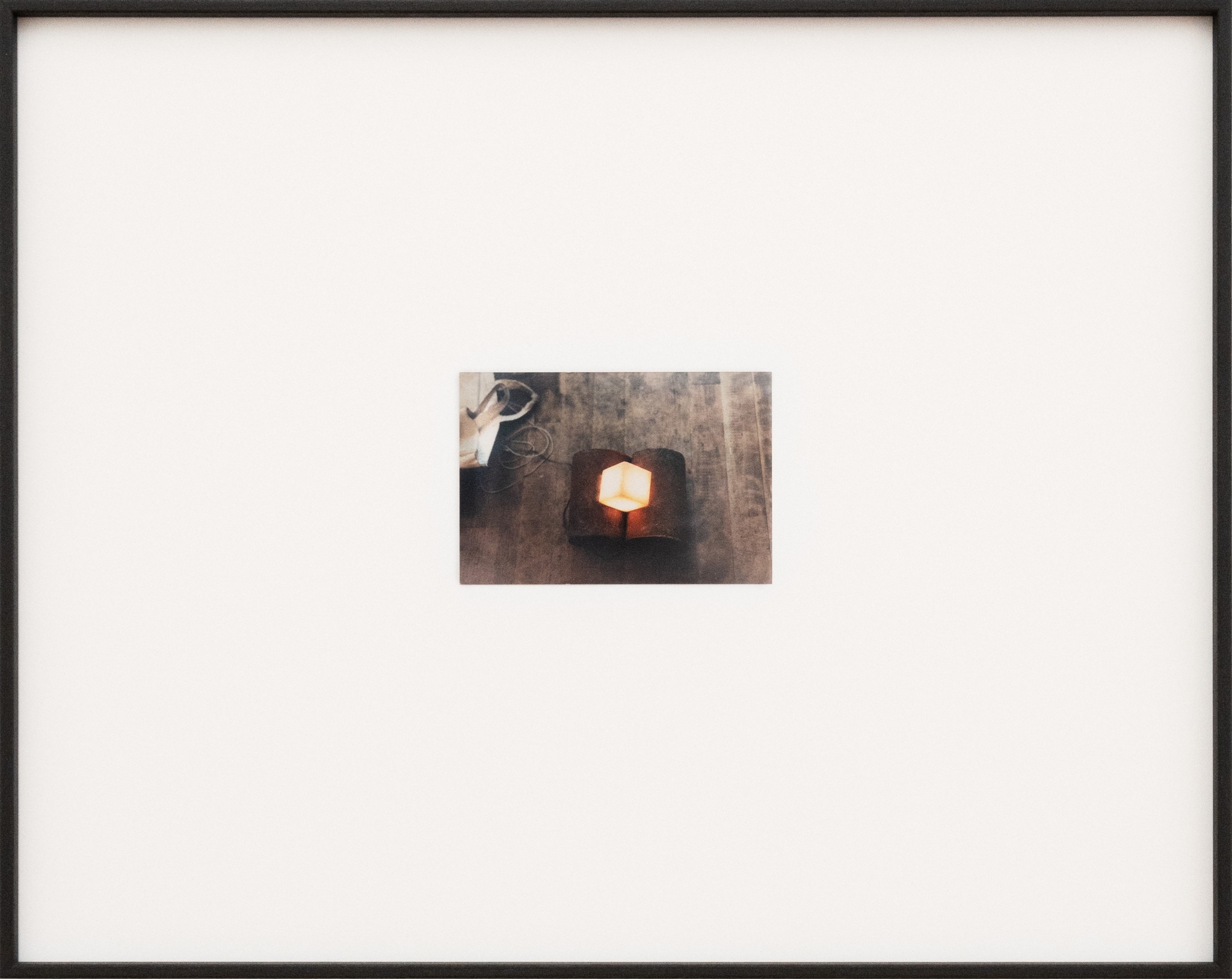

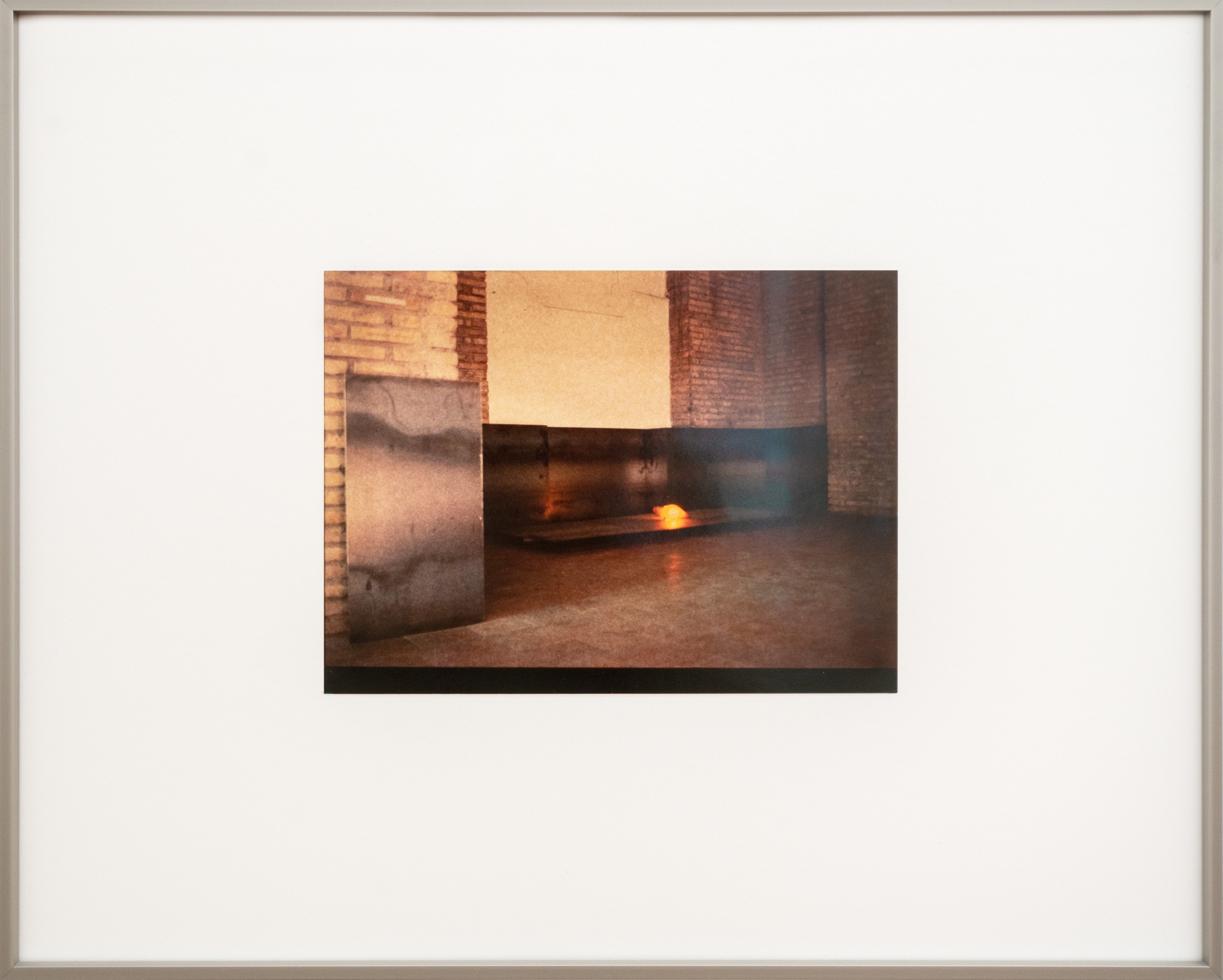

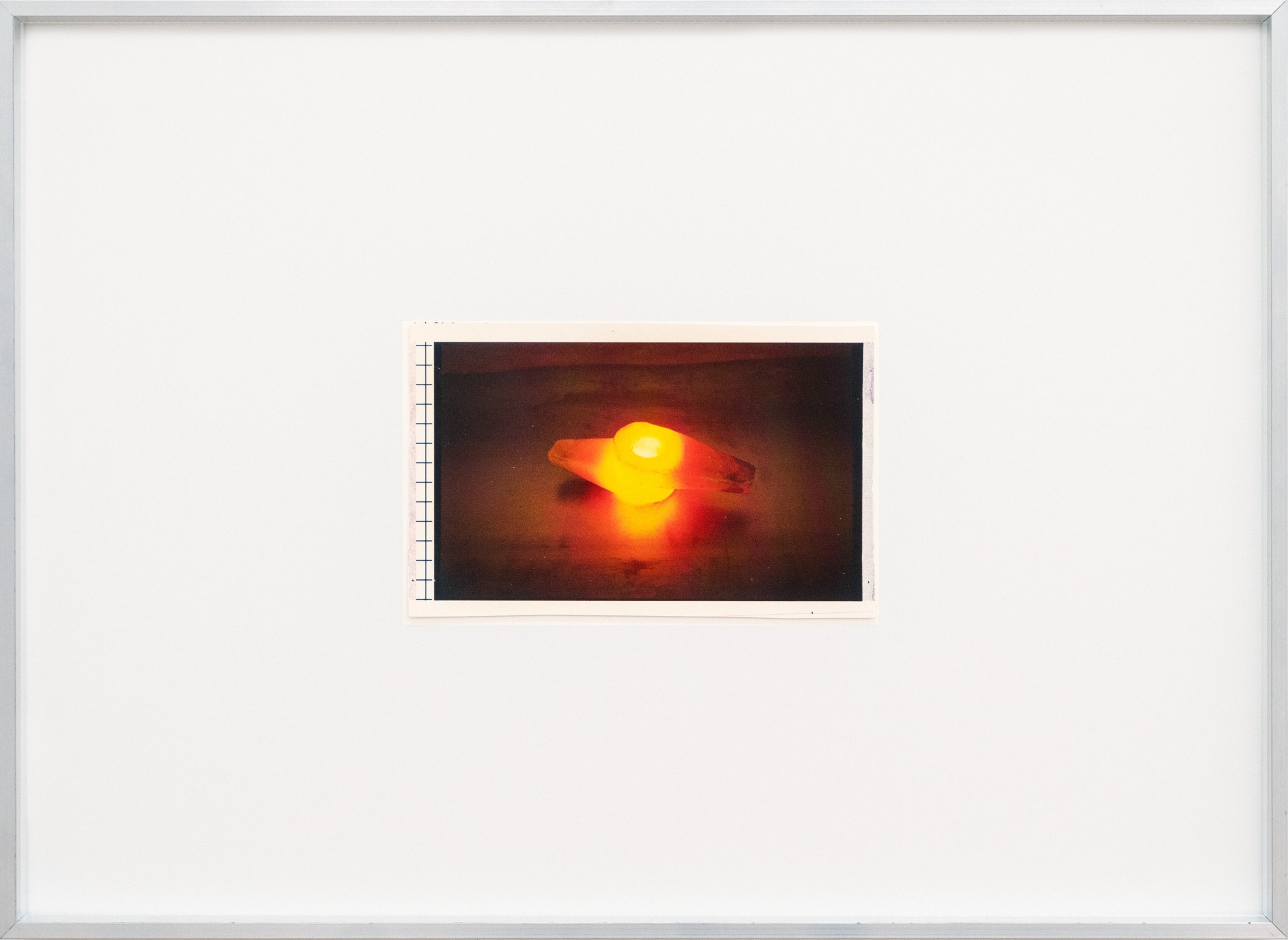

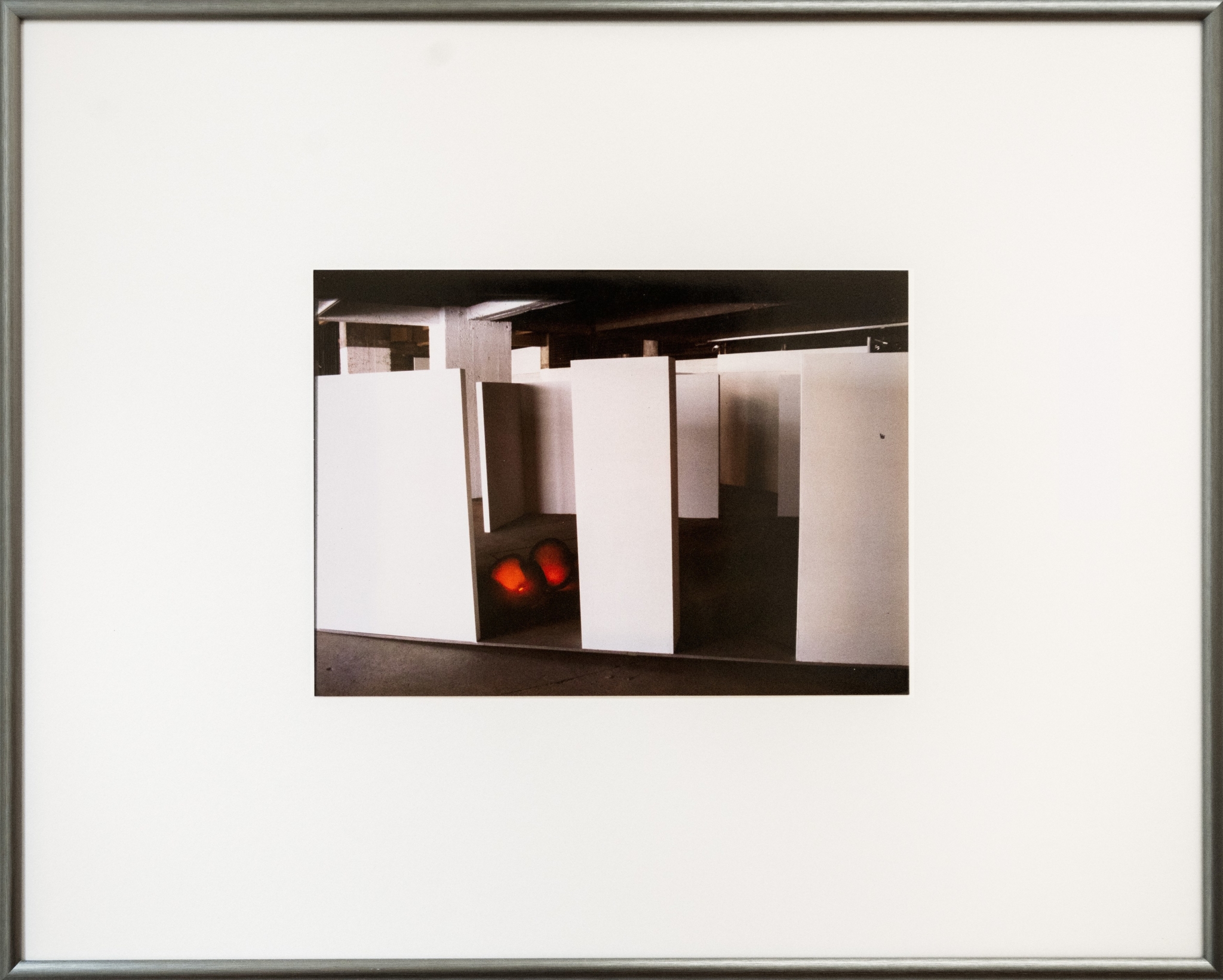

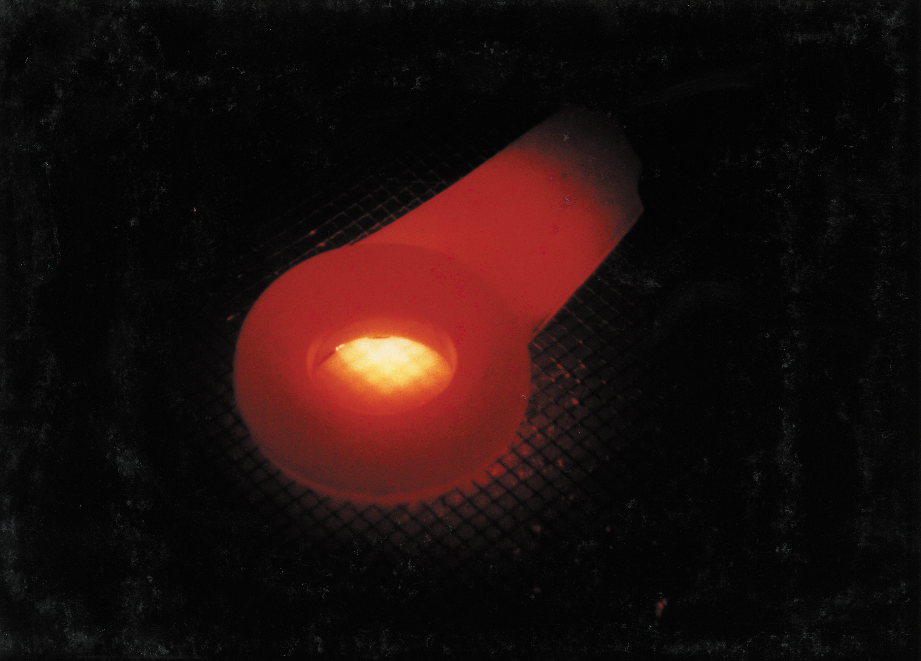

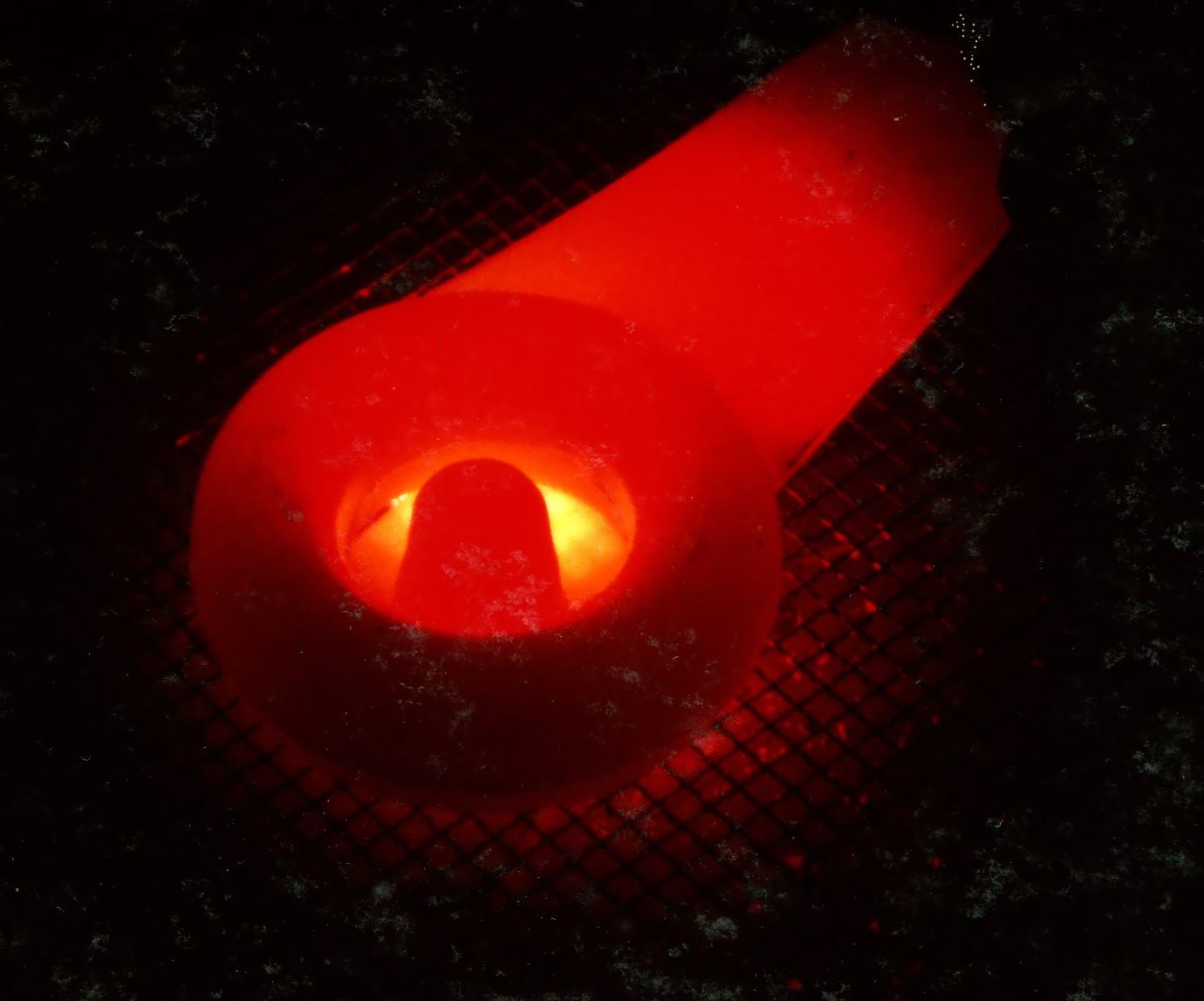

In the words of French writer, poet, and playwright Jean-Christophe Bailly, Tzivelos treated light as an event, both visual and sonic (“indeed, what noise does the sun make?”). Just from looking at his sculptures, one can see Tzivelos’ light as alive, organic, evolving, restless. The shimmering glow he produced by filtering light emanating from halogen lamps through wax and resin gives the impression of fecundity; of something about to be born, a fetus in the womb. Everything around it, the iron, the metal sheets, the bricks that lace the floor, or whatever other material serves to house the light, are the world as we know it, about to be transformed.

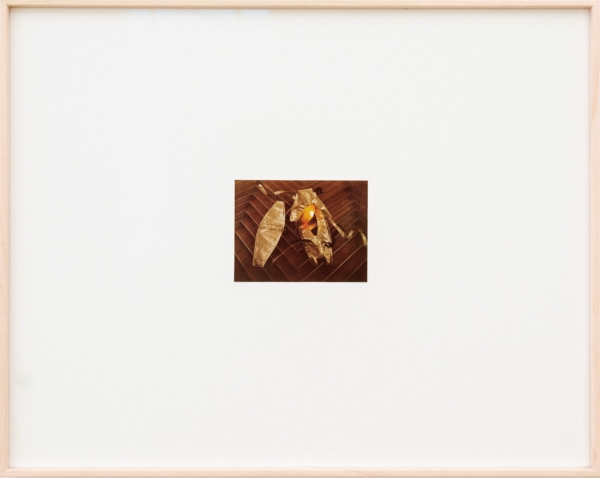

Bia Papadopoulou and Christopher Marinos have approached this fecundity in terms of Tzivelos’ active engagement with alchemy, as evidenced in his writings, drawings, and book collection. In terms of its ambiguous relation to chemistry, it could be said that alchemy concerned itself with the transmutation of base metals. Roughly speaking, transmutation refers to the belief that base metals can turn into gold when heated in fire. In the middle ages and beyond, many an alchemist could be found captive in royal enclaves, forced to perform alchemical experiments in the hopes of generating gold or finding the philosopher’s stone. It is said that an accidental byproduct of alchemical experimentation was the invention of porcelain in the West (long after China, of course). In correspondence with the various physical stages of transmutation, attributes or qualities like color acquired an added symbolic significance. More importantly, Rubedo, a Latin word meaning redness, was adopted by alchemists to define the fourth and final stage of their magnum opus, signaling the complete transmutation. The sequence of colour changes in alchemy is as follows: black gives way to white, which is succeeded by yellow, which finally redends into a deep burgundy or purple. These alchemical stages have acquired through the ages poetic, nearly mythological proportions. Many writers and theorists have latched onto them, ascribing them with parallel meanings. In psychological terms, Jung has famously described these as Confession, Illumination, Education, and Transformation, which in his analysis correspond with an individual’s journey towards fulfillment, also through love.

IV. Post-it

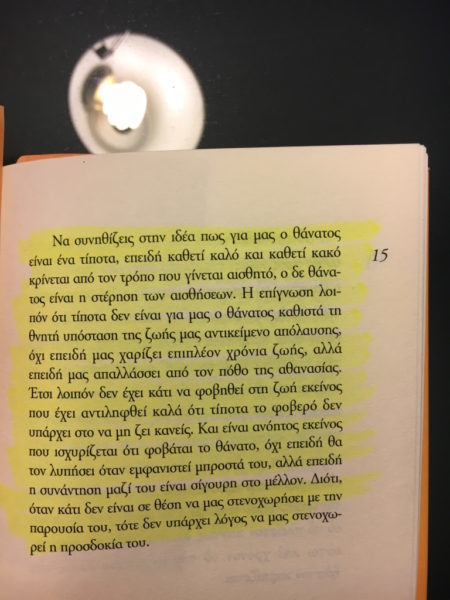

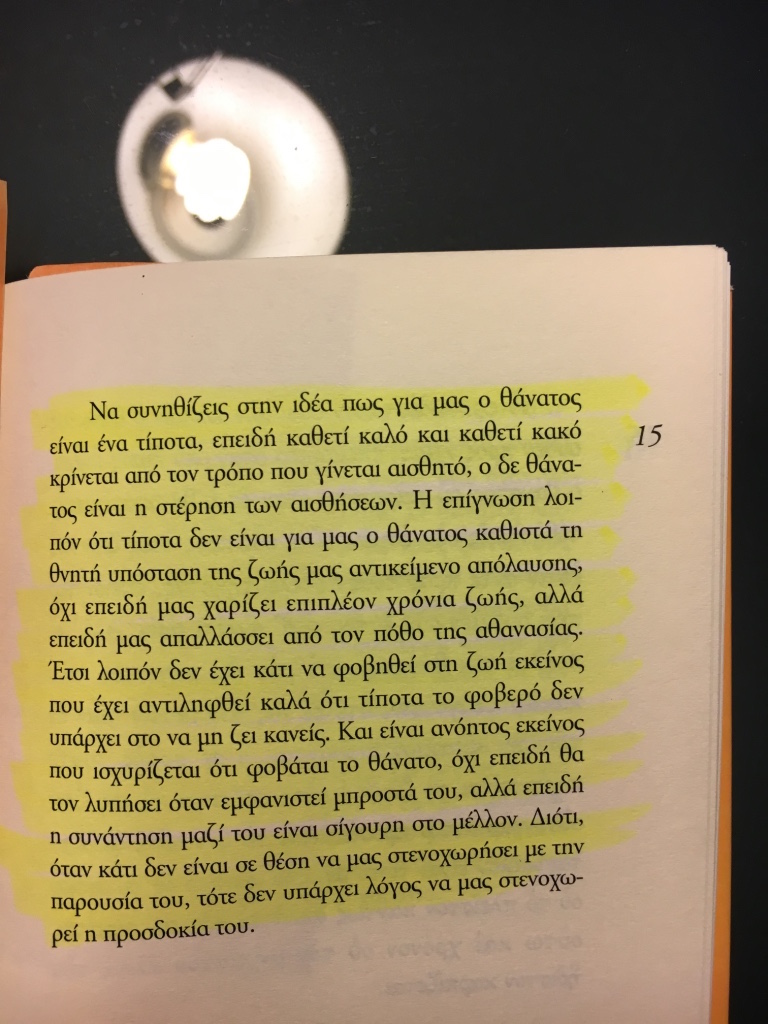

In the bookcase behind the desk, a single file full of folders filled with hundreds of sketches, post-it notes, clippings, drawings, slides, and photographs summarized Christos’ surfaces, stitching together a truncated chronology of his life and work. Post-it notes, in particular, he seemed to use as a fragmented diary where he’d write about more personal episodes in his life or note down ideas for artworks, aphorisms, or beautiful sentences. He was also an avid user of highlighters with entire segments of books made fluorescent; in his copy of Epicurus’ ‘Letter to Menoeceus,’ the third segment on death burns luminescent:

Become accustomed to the belief that death is nothing to us. For all good and evil consists in sensation, but death is deprivation of sensation. And therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not because it adds to it an infinite span of time, but because it takes away the craving for immortality. For there is nothing terrible in life for the man who has truly comprehended that there is nothing terrible in not living. So that the man speaks but idly who says that he fears death not because it will be painful when it comes, but because it is painful in anticipation. For that which gives no trouble when it comes, is but an empty pain in anticipation. So death, the most terrifying of ills, is nothing to us, since so long as we exist, death is not with us; but when death comes, then we do not exist. It does not then concern either the living or the dead, since for the former it is not, and the latter are no more.

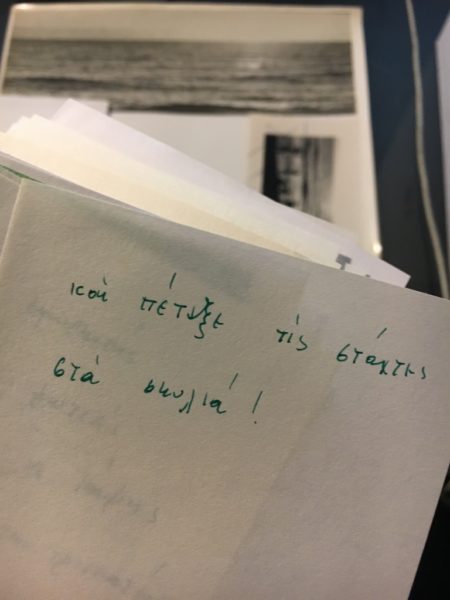

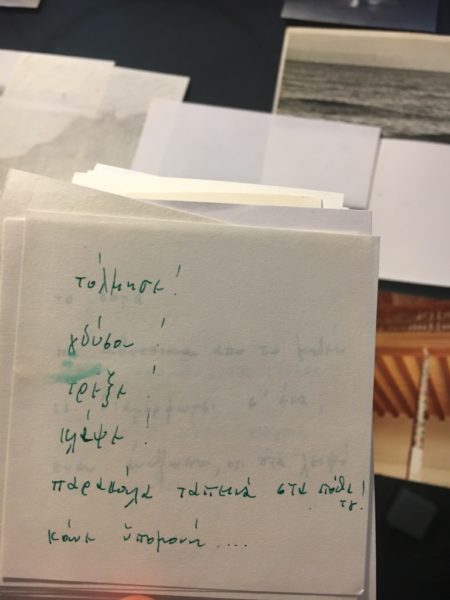

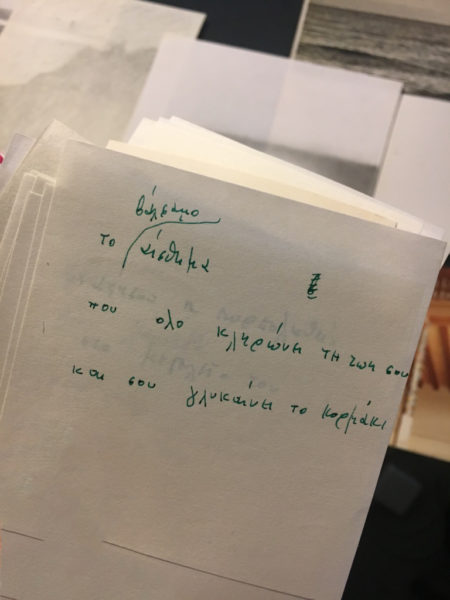

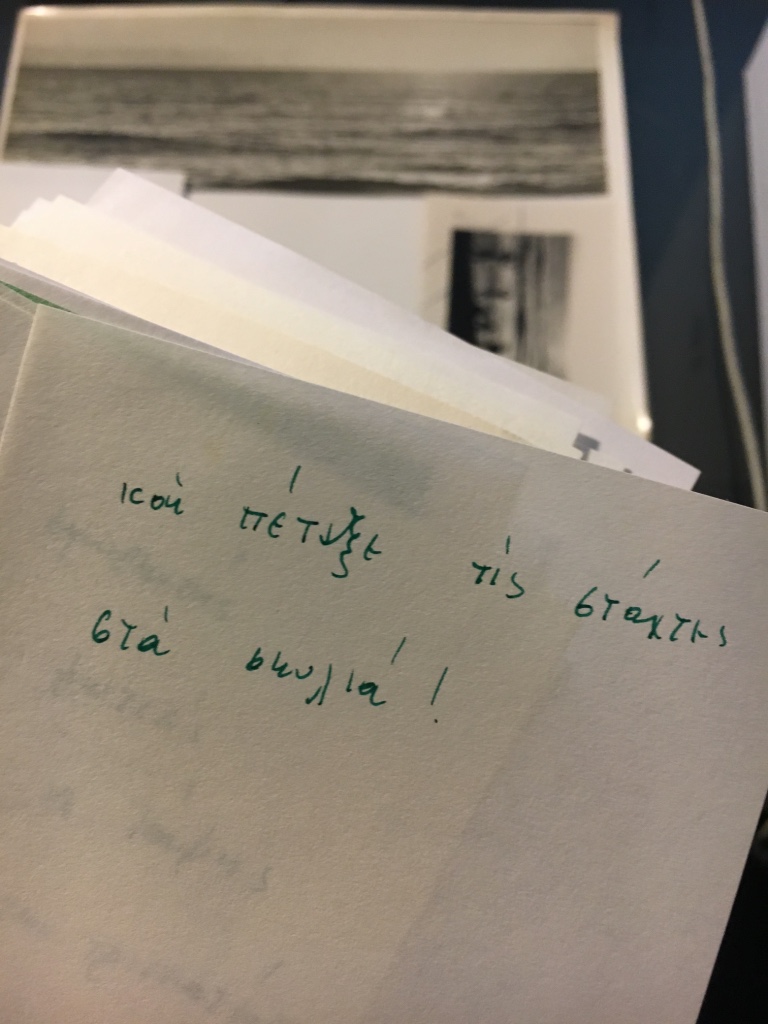

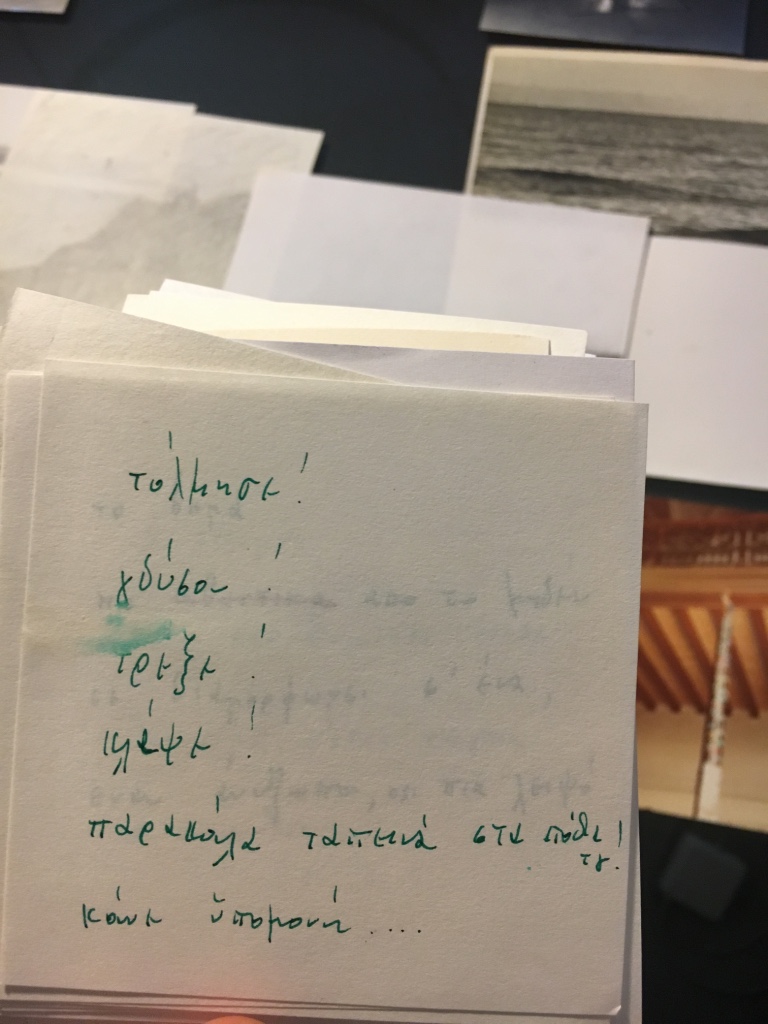

A series of post-it notes read like stage directions or lines whispered by a prompter:

“Be brave!/ Get undressed!/ Run!/ Cry!/ Beg humbly at his feet!/ Be patient …”

or

“Balsam/ the feeling of relief/ that dials your life/ and softens your body”

or

“Throw the ashes to the dogs!”

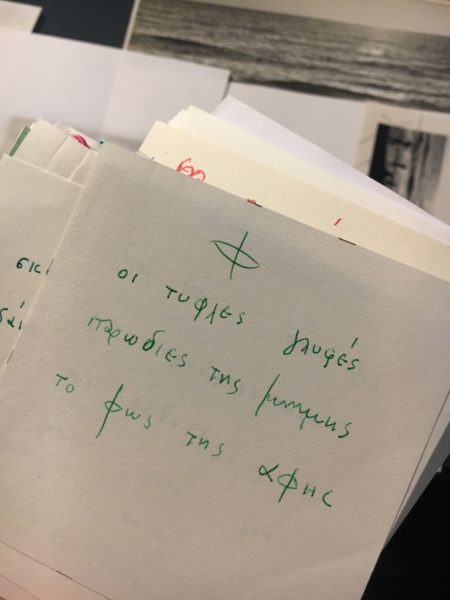

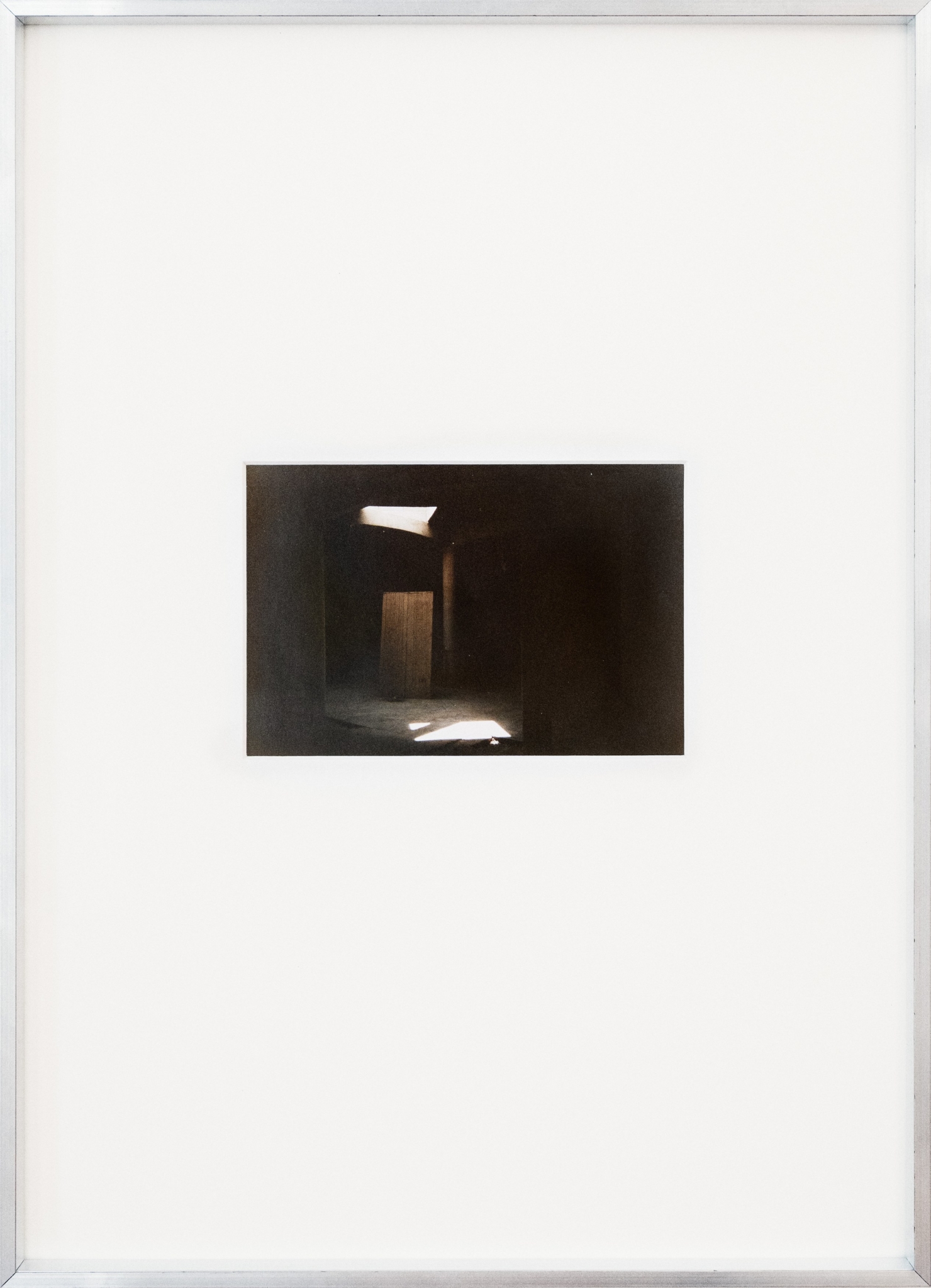

V. Rubedo dies out

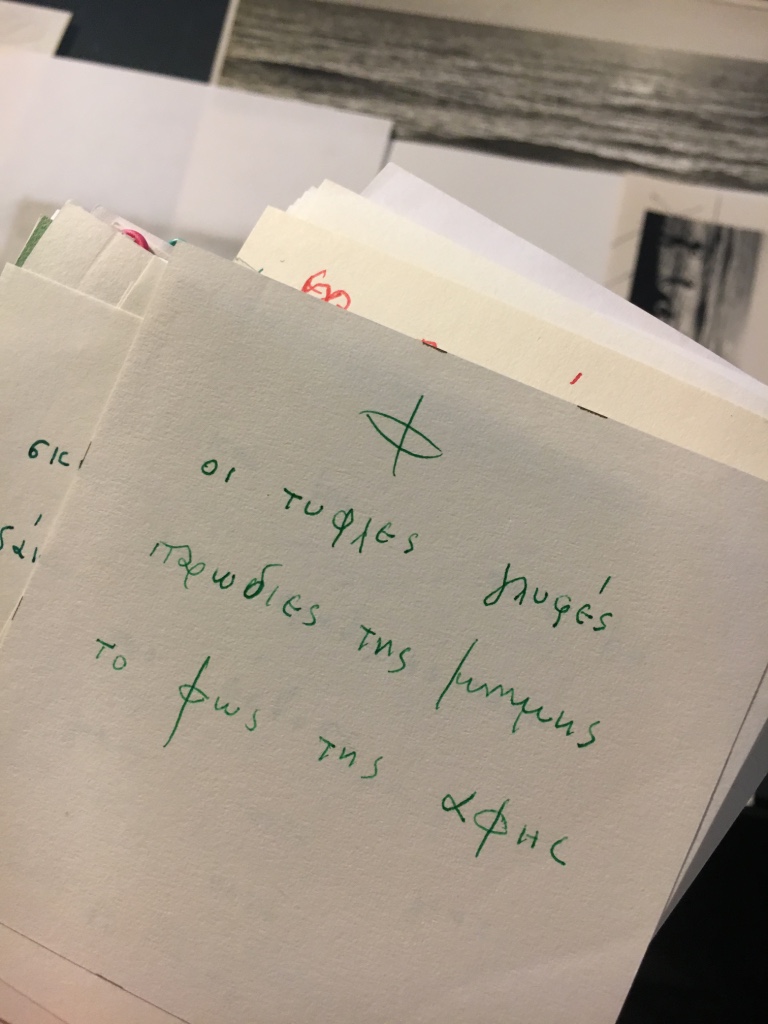

On an A4 paper, Tzivelos has noted down ideas for titles. Among these, there’s ‘Store in a Cool Place.’ A title that never lived out its life befits the show, which closes in on the photographic documentation left behind by Tzivelos; a portfolio of images either by him or install photographers documenting his work within exhibitions (site-specific installations) or at the studio. These are, in essence, the more resilient remnants of the works as circumstances that came and went. Different from the remaining installations conceived in-situ, which now live out a partial life elsewhere, these photographic prints situate his practice as event-based. Temperature and brightness become mediators of his legacy like they were formative for the work while he was still alive. Tzivelos used wax instead of resin to encase light. In the course of a show, lightbulbs would heat up and gradually melt their closeting wax. Tzivelos would return and recast the wax, maybe three times during an exhibition. Without visitors realizing, the light would escape into the room, then be recaptured, fighting a rhythmical battle against a material that was once part of a honeycomb. That same rhythmical reveal is present in the archive. For storage of printed photographs, low temperatures are recommended. Warmth-averse, conservation swerves away from the fire into the direction of coolness.

***

Christos Tzivelos (1949 – 1995) was an artist and set designer active in Athens and Paris from 1972 until his untimely death. He graduated in interior design from the Athens Technological Group, commonly known as Doxiadis School, in 1971; in fine art from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in 1976; and in architectural engineering from the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-La Vilette in 1990. He worked as an artist assistant for Costas Tsoclis and later Takis. While participating in exhibitions, he also designed theatre sets for directors Gilberte Tsai and Leonidas Strapatsakis for productions in Marseilles, Strasbourg, and Nice. Notable group shows include: ‘À Pierre et Marie: Une Exposition en Travaux’ at an abandoned cathedral in Paris (1982-1984), alongside Robert Barry, Daniel Buren, Tony Cragg, and Dan Graham, among others; ‘Sculptures: Première Approche pour un Parc’ at Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, Jouy-en-Josas (1985), alongside Carl Andre, Anthony Caro, Donald Judd, Mario Merz, and Isamu Noguchi, among others; and ‘l’espace, le temps’ at Fondation Danae, Pouilly (1986), alongside Alison Knowles, Charlemagne Palestine, and Ernest T., among others. Of special significance are a series of exhibitions titled ‘Il y a un an,’ curated by Catherine Arthus-Bertrand in Paris, New York, and Rome, initiated in 1985. Notable solo shows include: ‘Pyro’ at Medusa Art Gallery, Athens (1986), ‘Carte Blanche’ at Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, Paris (1989), and ‘One Man Show’ at Galerie Renos Xippas, Paris (1993). Posthumously, a retrospective exhibition titled ‘Modelling Phenomena’ was organised by Christopher Marinos and Bia Papadopoulou at Benaki Museum in Athens (2017), accompanied by a catalogue designed by Studio Lialios Vazoura, and published under the imprint Big black mountain the darkness never ever comes.

***

All works courtesy of Yiannis Tzivelos. The exhibition was made possible through the support of Carved to Flow Foundation, Nigeria. With thanks to Yiannis Tzivelos, Bia Papadopoulou, Christopher Marinos, Aris Mochloulis, Erasmia Kadinopoulou, and Sdralis Artworks.